“She had a mezzo-soprano voice, that was less clear than penetrating. Her execution was articulate and brilliant. She had a fluent tongue for pronouncing words rapidly and distinctly, and a flexible throat for divisions, with so beautiful a shake that she put it in motion upon short notice, just when she would. In her action she was very happy; and as her performance possessed that flexibility of muscles and face-play, which constitute expression, she succeeded equally well in furious, tender, and amorous parts. In short, she was born for singing and acting”. High words of praise indeed, specifically since they were reported by famed composer and theorist Johann Joachim Quantz and subsequently retold by Charles Burney. Her nickname was the “New Siren”, but she was commonly known simply as “Faustina”. Born in Venice in 1697, Faustina Bordoni was universally ranked among the greatest singers of her age. Ravishingly beautiful—with brilliant large black eyes, splendid hair, a fascinating sweetness of expression and regal manners, Faustina quickly conquered the operatic stages and yearning hearts of numerous wealthy gentlemen throughout Europe.

“She had a mezzo-soprano voice, that was less clear than penetrating. Her execution was articulate and brilliant. She had a fluent tongue for pronouncing words rapidly and distinctly, and a flexible throat for divisions, with so beautiful a shake that she put it in motion upon short notice, just when she would. In her action she was very happy; and as her performance possessed that flexibility of muscles and face-play, which constitute expression, she succeeded equally well in furious, tender, and amorous parts. In short, she was born for singing and acting”. High words of praise indeed, specifically since they were reported by famed composer and theorist Johann Joachim Quantz and subsequently retold by Charles Burney. Her nickname was the “New Siren”, but she was commonly known simply as “Faustina”. Born in Venice in 1697, Faustina Bordoni was universally ranked among the greatest singers of her age. Ravishingly beautiful—with brilliant large black eyes, splendid hair, a fascinating sweetness of expression and regal manners, Faustina quickly conquered the operatic stages and yearning hearts of numerous wealthy gentlemen throughout Europe.

The “Old Siren” Francesca Cuzzoni also inspired glowing professional accolades. Quantz describes “her style of singing as innocent and affecting, and her ornaments took possession of the soul of every auditor, by her tender and touching expression.” Giovanni Battista Mancini, in turn, reports, “So grateful and touching was her natural tone that she rendered pathetic whatever she sang, when she had the opportunity to unfold the whole volume of her voice. Her power of conducting, sustaining, increasing, and diminishing her notes by minute degrees acquired for her the credit of being a complete mistress of her art. Her high notes were unrivaled in clearness and sweetness, and her intonation was so absolutely true that she seemed incapable of singing out of tune.” Daughter of a professional violinist, Francesca originally hailed from Parma but quickly secured appointments throughout Italy and continental Europe. Reports of her physical appearance commonly emphasised beady eyes, a large nose and a triple chin. In addition, she was said to possess a turbulent and obstinate temper, was conceited, insolent, and supposedly ungrateful.

Handel: Admeto, HWV 22 (1727)

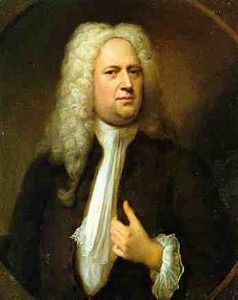

The third queen in this story, of course, is George Friedrich Handel. The question of his sexual orientation has kept countless writers awake over the centuries. In the end, however, since Handel treated his amorous tendencies and excursions with complete privacy, it really depends on which faction of the supposedly scholarly discourse you would like to believe. Mainstream musicology has generally ignored the issue—as they almost always do—and the far right eagerly portrait him as a very shy and timid heterosexual individual; clearly the creator of the Messiah can’t be gay! Meanwhile, queer theory is determined to claim him as another suppressed kindred spirit—they are less enthusiastic when it comes to people like Adolf Hitler—and the great postmodern egalitarianism endlessly debates the epistemological absence of the word “homosexuality” during Handel’s time. Whether he conceptually or physically loved either Faustina or Francesca or both—it seems he might have been more comfortable with the castrato Senesino—is of secondary importance. What is significant after all, is the fact that he composed tailor-made roles for both queens of the lyric stage.

The third queen in this story, of course, is George Friedrich Handel. The question of his sexual orientation has kept countless writers awake over the centuries. In the end, however, since Handel treated his amorous tendencies and excursions with complete privacy, it really depends on which faction of the supposedly scholarly discourse you would like to believe. Mainstream musicology has generally ignored the issue—as they almost always do—and the far right eagerly portrait him as a very shy and timid heterosexual individual; clearly the creator of the Messiah can’t be gay! Meanwhile, queer theory is determined to claim him as another suppressed kindred spirit—they are less enthusiastic when it comes to people like Adolf Hitler—and the great postmodern egalitarianism endlessly debates the epistemological absence of the word “homosexuality” during Handel’s time. Whether he conceptually or physically loved either Faustina or Francesca or both—it seems he might have been more comfortable with the castrato Senesino—is of secondary importance. What is significant after all, is the fact that he composed tailor-made roles for both queens of the lyric stage.

Francesca had been in London since 1722, and Handel provided her with the role of Teofane in the opera Ottone, which opened the fourth season for the Royal Academy of Music. Francesca apparently refused to sing at rehearsal, and an indignant Handel grabbed her roughly by the waist and threatened to fling her out of the window. Nevertheless, Handel took great care to accentuate the lyrical qualities of her voice, and within days, she had become a celebrity. Things took a turn for the worse, when Handel rather innocently persuaded Faustina to join them in London in 1726. During the next two years, Handel tailored five roles for Faustina’s vocal and artistic qualities—probably most memorable was her role as Roxana in Allessandro – but the two leading ladies of the stage were soon engaged in a bitter feud, with London audiences equally divided in support of Francesca or Faustina. Handel desperately tried to keep the peace, and his opera Admeto, re di Tessaglia of 1727—featuring Faustina, Senesino and Cuzzoni—is generally considered his finest musical pleas for calm. Yet things quickly deteriorated when both Sirens appeared on the same stage in Bononcini’s Astianatte in 1727. Inspired by a thoroughly misbehaving audience, the two primadonne soon stopped singing altogether and instead traded left hooks and uppercuts. Their public tussle was even immortalized in a burlesque farce entitle “The Rival Queens”, and the bard Ambrose Philips wisely penned the following lines:

“Little sirens of the stage,

Charmer of an idle age,

Empty warblers, breathing lyre,

Wanton gale of fond desire;

Bane of every manly art,

Sweet enfeeblers of the heart;

Oh! too pleasing is thy strain.

Hence to southern climes again,

Tuneful mischief, vocal spell;

To this island bid farewell:

Leave us as we ought to be—

Leave the Britons rough and free.”

And so they did! Francesca accepted an engagement in Vienna and Faustina returned to Venice to find the love of her life, but that’s clearly a different story.

More Love

- Untangling Hearts

Klaus Mäkelä and Yuja Wang What happens when two brilliant musicians fall in love - and then fall apart? -

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more - Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music?