Alphonse Allais

Although his piece is the most famous, 4’33” by John Cage wasn’t the first silent piece to be written. There are at least two earlier works that also take up the sound of silence.

Alphonse Allais (1854-1905) wasn’t a composer at all but a writer and humourist. One poetic style he liked was holorhyme, where entire lines are pronounced the same way, although spelled differently:

Par les bois du djinn où s’entasse de l’effroi,

Parle et bois du gin, ou cent tasses de lait froid.

By the woods of the Djinn where dread heaps up,

Talk about and drink gin, or a hundred cups of cold milk.

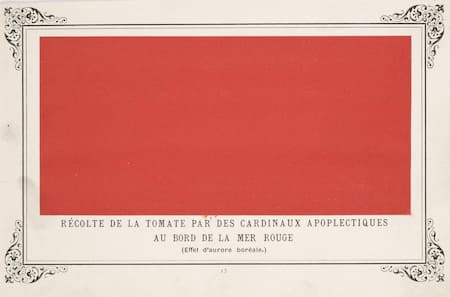

He created a series of mono-colour images: the all-red one, entitled Récolte de la tomate par des cardinaux apopletiques au bord de la Mer Rouge (effet d’aurore boréale.) (Apoplectic Cardinals Harvesting Tomatoes on the Shore of The Red Sea (Study of the Aurora Borealis)) dates from 1884.

Allais: Récolte de la tomate par des cardinaux apopletiques au bord de la Mer Rouge

(effet d’auorre boréale.), 1884

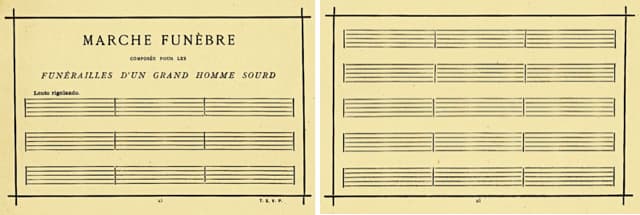

His 1897 work, Marche funèbre composée pour les funérailles d’un grand homme sourd (Funeral March for the Obsequies of a Deaf Man) consists of 24 blank measures. In his preface, Allais writes:

L’auteur de cette Marche funèbre s’est inspiré, dans sa composition, de ce principe, accepté par tout le monde, que les grandes douleurs sont muettes.

Le grandes douleurs étant muettes, les exécutants devront uniquement s’occuper a compter des mesures, au lieu de se livrer à ce tapage indécent qui retire tout caractère auguste aux meilleurs obsèques.

The author of this Funeral March was inspired in its composition by this principle, accepted by everyone, that great sorrows are silent.

The great sorrows being silent, the performers will only have to occupy themselves with counting measures, instead of indulging in this indecent noise which removes all august character from the best funerals.

From the title, everyone assumes this is just a Funeral March for a deaf man, whereas it actually has a different intent: it’s a funeral march that doesn’t bother the funeral attendees!

Allais: Marche funèbre composée pour les funérailles d’un grand homme sourd

Oddly, there is no recording of this work.

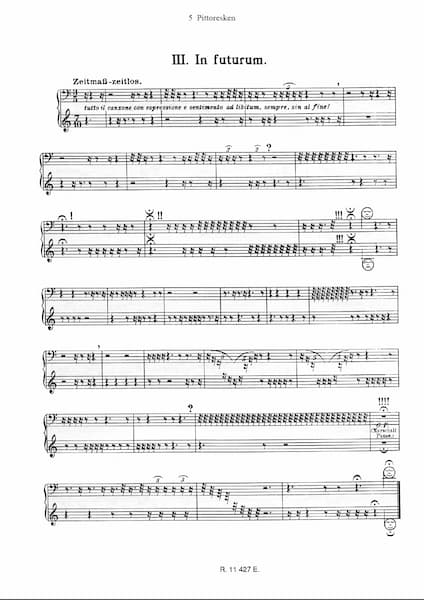

Erwin Schulhoff

In his 1919 work, 5 Pittoresken, Op. 31, Dadaist Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) took his love of jazz and created a 5-movement work that captured the jazz feeling in the air. The movements are all named for dances: foxtrot, ragtime, one-step, maxixe (or Brazilian Tango, a kind of two-step). The middle movement, however, entitled ‘In futurum,’ was silent, although fully written out in the score. The score consisted of one page in impossible time signatures, with each measure filled out with rests.

Schulhoff: In Futurum

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Pittoresken, Op. 31 – No. 3. In futurum (Caroline Weichert, piano)

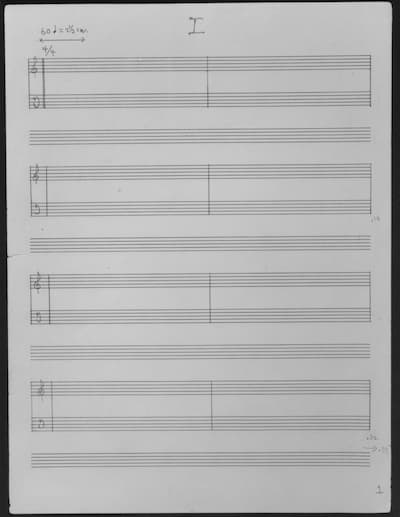

John Cage

The most famous work by the American composer John Cage is his 4’33”, written in 1952. This three-movement piece was given its premiere by pianist David Tudor, who signaled the beginning of the first movement by opening the cover of the keyboard, ended the first movement by closing the cover, and performed the second and third movements the same way. What that first audience heard as the piece, but perhaps didn’t understand, was that what happened in sound between the opening and closing of the keyboard cover was the piece itself: the ambient noise of the hall, a brief rainstorm in the second movement, and, in the third movement the audience themselves as ‘they talked or walked out.’ The original score is lost, but here is the pianist David Tudor’s reconstruction of the first movement.

Cage: 4’33”, reconstructed by David Tudor

John Cage: 4′ 33” (Floraleda Sacchi, harp)

Cage would later write as work often referred to as 4’33’ No. 2, but which was actually called 0’00”, dedicated to Yoko Ono, where the score consisted of this sentence: ‘In a situation provided with maximum amplification, perform a disciplined action.’ The first performance of the piece was Cage writing that sentence. More rules were added at the next performance: ‘the performer should allow any interruptions of the action, the action should fulfill an obligation to others, the same action should not be used in more than one performance, and should not be the performance of a musical composition.’

Each composer used silence in a different way. Allais, an artist, used silence as a commentary on what he would like to hear at a funeral, to reflect the great sorrow of a death. For Schulhoff, who loved jazz and dancing, the score, with its impossible demands on the performer, fit in with his Dadaist world. John Cage, on the other hand, wanted people to really listen to the world around them. It was only in the formality of a concert presentation, where all attention is focused on a performer at the front of the hall, that he was able to command the listener’s attention and then fed it by giving it nothing additional than the world around them to listen to.

So we don’t end in complete silence, here are the other movements of Schulhoff’s 5 Pittoresken.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Pittoresken, Op. 31 (Caroline Weichert, piano)