In 1871, the loss of Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) led to a musical movement in France to strive for a real “Frenchness” of music. Under the leadership of Camille Saint-Saëns and Vincent d’Indy, Société Nationale de Musique adopted the motto “Ars Gallica (French Art),” hosting concerts for new compositions by French composers. Many significant French composers were associated with Société Nationale de Musique.

In 1871, the loss of Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) led to a musical movement in France to strive for a real “Frenchness” of music. Under the leadership of Camille Saint-Saëns and Vincent d’Indy, Société Nationale de Musique adopted the motto “Ars Gallica (French Art),” hosting concerts for new compositions by French composers. Many significant French composers were associated with Société Nationale de Musique.

The majority of composers in Société Nationale de Musique were male, but there were active female composers whose works were regularly performed. While Cécile Chaminade, Lili Boulanger, and Pauline Viardot are better-known composers, this article will introduce three forgotten female composers who were actively involved in the organization: Augusta Holmès (1843-1871), Clémence de Grandval (1828-1907), and Marie Jaëll (1846-1925). Their influences on French music and the music scene were nothing less than their male counterparts.

Augusta Holmès (1843-1871)

Augusta Holmès

Holmès had a successful career as a musician throughout her life. She was born to Irish parents interested in art and literature. When Augusta was very young, her musical talent became obvious. However, Mrs. Holmès was a painter and did not encourage her daughter to pursue music. Instead, she tried many ways to discourage her daughter’s interest in music. At age 11, when her mother passed away, Augusta began to study music seriously. She started to take lessons with Henri Lambert and Hyacinthe Klosé. Because she was a female, she was not accepted to study at the Paris Conservatoire. However, her talent was widely recognized by some famous composers of the time. Her talent and beauty also attracted Camille Saint-Saëns and César Franck, who became her lifelong friend and teacher, respectively. Saint-Saëns called her “an extremist” in the journal Harmonie et Mélodie.

Her musical output was substantial, she wrote 12 symphonic poems, four operas, and over 100 songs throughout her life. Numbers of her works were performed under the occasion by Société Nationale de Musique. While most of the compositions only had one performance, Holmes’ symphonic poem Iriande was heard on three different occasions, and her Pologne was performed twice.

Augusta Holmès: Irlande (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Samuel Friedmann, cond.)

Augusta Holmès: Pologne (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Samuel Friedmann, cond.)

Liszt and Wagner had both expressed admiration for Holmès’ songs; Liszt once said her songs were as good as Schubert’s.

La Haine – Les sept ivresses – Augusta Holmès – Duo Moine ou Voyou

Clémence de Grandval (1828-1907)

Clémence de Grandval

Unlike Augusta Holmès, Clémence de Grandval was fully supported by her family in her music career. Born to a wealthy family, her father was awarded the officer of Legion of Honour, and her mother was a writer. Grandval began taking music lessons at a very young age. Her teachers included Frédéric Chopin and Camille Saint-Saëns. She won the Prix Rossini in 1881.

Grandval did not stop composing even after she married Vicomte de Grandval, although she could not use her real name to publish her works anymore. Instead, she used pseudonyms included Caroline Blangy, Clémence Valgrand, Maria Felicita de Reiset, and Maria Reiset de Tesier. Her works include operas and popular songs. She also wrote many instrumental works, especially works for the oboe. She was the most played female composer in the Société Nationale de Musique. My favorite pieces include her Suite for flute and piano, Four Pieces for cor anglaise, and Valse mélancolique. They were both performed for the organization.

Clémence de Grandval: Flute Suite (Kenneth Smith, flute; Paul Rhodes, piano)

Clémence de Grandval: Quatre Pieces Pour Cor Anglais

Grandval was a successful living composer, however, her fame did not continue when she passed away in 1907. Unfortunately, her works are not performed as frequently as they were used to be.

Clémence de Grandval: Valse mélancolique

Marie Jaëll (1846-1925)

Marie and Alfred Jaëll

As a pianist, I was particularly excited when I discovered Marie Jaëll. She was a pianist, composer, and pedagogue who attempted to replace the traditional piano methods. Before studying at the Paris Conservatory with Heinrich Herz, she took piano lessons with F.B. Hamma and Ignaz Moscheles. She gained public recognition as a pianist when she was a teenager, and she was the first pianist to perform all 32 piano sonatas by Beethoven in Paris. Later in her life, she took composition lessons with Camille Saint-Saëns and César Franck. Saint-Saëns thought highly of her; he not only dedicated his Piano Concerto No. 1 and the “Étude en forme de valse” to her, but he also introduced her to the Société Nationale de Musique. Jaëll was an active member of the organization as both performer and composer. Her compositions include piano, choral works, concertos, and string ensembles, including her Cello Concerto in F Major, which she dedicated to Jules Delsart.

Marie Jaëll: Cello Concerto in F Major (Xavier Phillips, cello; Brussels Philharmonic Orchestra; Hervé Niquet, cond.)

Marie Jaëll

Marie Jaëll was married to Alfred Jaëll when she was twenty years old. Alfred Jaëll was a well-known Austrian pianist of the time. The couple often performed four-hand repertoire together, focusing on contemporary music. However, Alfred died in 1882, and Marie remained single for the rest of her life.

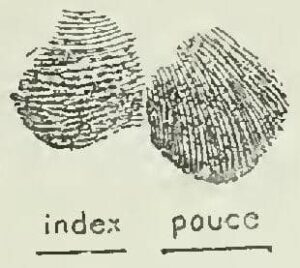

Marie Jaëll’s fingerprints photographs

on piano touch

She devoted herself entirely to music, especially to piano pedagogy. Her book, Le Toucher, Nouveaux principes élémentaires pour l’Enseignement du Piano (“Touch, new basic principles for piano teaching”), states the importance of hand motions through the physiological approach. She added fingerprints photographs to analyze the piano touch in the revised edition.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Marie Jaëll: Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor (Romain Descharmes, piano; Lille National Orchestra; Joseph Swensen, cond.)

Marie Jaëll: Voix du printemps: 6 Pieces for piano 4-hands

Great showcase of really good music. Some of it above what was composed by other contemporaries of the same époque. That it has not been recorded it must be surely ignorance or myopia!

The title on the first page seems part of the problem. To add an admiration sign (!) to “were composers” is, quite frankly, passé. Nobody with more than basic musical knowledge should be surprised anymore that women could and can compose VERY WELL. It is those who decide what to record the ones who carry the prejudice.