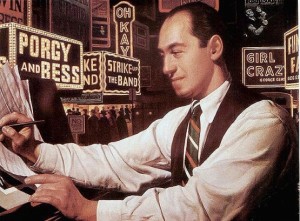

However you’d like to look at it, George Gershwin was unique! Freely mixing and combining classical and popular music styles, his works have been heralded as representing “an exciting new American musical art.” Yet when it came to Porgy and Bess, the racial aspects of the opera elicited rather severe public and critical reaction. The composer Virgil Thomson called it “crooked folklore and half-way opera, a strong but crippled work with recitatives as ineffective as anything I’ve heard. He also slammed Gershwin’s “fidgety accompaniments, over-rich and vulgar scoring, gefilte fish orchestration and lack of understanding of all the major problems of form, continuity and serious or direct musical expression.” But the most scathing censure came from black artists at the time. Duke Ellington wrote “Gershwin has borrowed from everyone from Liszt to a kazoo band but has only produced lampblack Negroisms.” One bizarre critic suggested, “the cast members needed to be darker, or at least to make themselves up, and the opera was called “a superficial and invidious form of Negroesque minstrelsy.”

However you’d like to look at it, George Gershwin was unique! Freely mixing and combining classical and popular music styles, his works have been heralded as representing “an exciting new American musical art.” Yet when it came to Porgy and Bess, the racial aspects of the opera elicited rather severe public and critical reaction. The composer Virgil Thomson called it “crooked folklore and half-way opera, a strong but crippled work with recitatives as ineffective as anything I’ve heard. He also slammed Gershwin’s “fidgety accompaniments, over-rich and vulgar scoring, gefilte fish orchestration and lack of understanding of all the major problems of form, continuity and serious or direct musical expression.” But the most scathing censure came from black artists at the time. Duke Ellington wrote “Gershwin has borrowed from everyone from Liszt to a kazoo band but has only produced lampblack Negroisms.” One bizarre critic suggested, “the cast members needed to be darker, or at least to make themselves up, and the opera was called “a superficial and invidious form of Negroesque minstrelsy.”

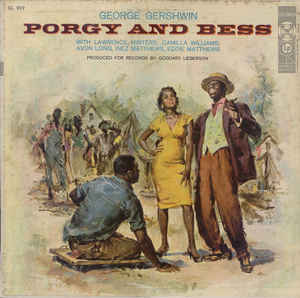

George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess, “Bess you is my woman now”

For its 30 September 1935 premier performance in Boston, the creative team consisting of George Gershwin, the librettist DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin had insisted upon an all-black cast. This proved to be challenging for various reason, including the fact that the entire cast was classically trained and had to re-learn colloquial inflection. Todd Duncan, the head of the music Department of Howard University who was to play Porgy, did not like jazz and auditioned with a recital of lieder and classical arias. The decision to use an all-black cast was born from the disastrous 1922 “colored Harlem tragedy enacted in the operatic style” titled Blue Monday. Vi is the sweetheart of Joe, a gambler, and she resists the advances of Tom the entertainer. Joe tells his boss that with his latest winning he intends to visit his mother, but ashamed of his sentiment, he refuses to let Vi see a telegram from his mother. Tom suggests to Vi that the telegram is from another woman. In a bout of jealously and rage, Vi shoots Joe. She eventually learns the truth and collapses while Joe sings his final farewell. Teetering on the brink of parody, Blue Monday was performed by white singers in blackface. Critics slammed it as “the most dismal, stupid and incredible black-face sketch that has probably ever been perpetrated.”

For its 30 September 1935 premier performance in Boston, the creative team consisting of George Gershwin, the librettist DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin had insisted upon an all-black cast. This proved to be challenging for various reason, including the fact that the entire cast was classically trained and had to re-learn colloquial inflection. Todd Duncan, the head of the music Department of Howard University who was to play Porgy, did not like jazz and auditioned with a recital of lieder and classical arias. The decision to use an all-black cast was born from the disastrous 1922 “colored Harlem tragedy enacted in the operatic style” titled Blue Monday. Vi is the sweetheart of Joe, a gambler, and she resists the advances of Tom the entertainer. Joe tells his boss that with his latest winning he intends to visit his mother, but ashamed of his sentiment, he refuses to let Vi see a telegram from his mother. Tom suggests to Vi that the telegram is from another woman. In a bout of jealously and rage, Vi shoots Joe. She eventually learns the truth and collapses while Joe sings his final farewell. Teetering on the brink of parody, Blue Monday was performed by white singers in blackface. Critics slammed it as “the most dismal, stupid and incredible black-face sketch that has probably ever been perpetrated.”

George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess, “It Ain’t Necessarily So”

Gershwin defended criticism that Porgy and Bess was less a serious opera than an excuse to string together a set of songs, but in the process fueled a critical confusion by proclaiming, “it represented a new genre, a folk opera.” He explained: “Because Porgy and Bess deals with Negro life in America it brings to the operatic form elements that have never before appeared in opera, and I have adopted every method to utilize the drama, the humor, the superstitions, the religious fervor, the dancing and the irrepressible high spirit of the race. If in doing this I have created a new form which combines opera and theater, then this new form has grown quite naturally out of the material.” Porgy and Bess had an initial run of 124 performances on Broadway, and it became the first American opera to be performed at La Scala in 1955. Hollywood produced a movie adaptation in 1959, with Harry Belafonte refusing the lead role because “all that crapshooting and razors and lust and cocaine is the old conception of the Negro.” It took until the 1970s for the social controversy to largely subside, and as such the work could be seen as a period piece. Currently, the Gershwin estate continues to tightly control the licensing of Porgy and Bess, and only allows productions of the opera with black performers.

Gershwin defended criticism that Porgy and Bess was less a serious opera than an excuse to string together a set of songs, but in the process fueled a critical confusion by proclaiming, “it represented a new genre, a folk opera.” He explained: “Because Porgy and Bess deals with Negro life in America it brings to the operatic form elements that have never before appeared in opera, and I have adopted every method to utilize the drama, the humor, the superstitions, the religious fervor, the dancing and the irrepressible high spirit of the race. If in doing this I have created a new form which combines opera and theater, then this new form has grown quite naturally out of the material.” Porgy and Bess had an initial run of 124 performances on Broadway, and it became the first American opera to be performed at La Scala in 1955. Hollywood produced a movie adaptation in 1959, with Harry Belafonte refusing the lead role because “all that crapshooting and razors and lust and cocaine is the old conception of the Negro.” It took until the 1970s for the social controversy to largely subside, and as such the work could be seen as a period piece. Currently, the Gershwin estate continues to tightly control the licensing of Porgy and Bess, and only allows productions of the opera with black performers.

George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess, “Summertime”

Porgy and Bess is an American classic, and Gershwin clearly wanted the depiction of an African-American community in crisis to have authenticity. However, there have been growing calls that this opera should embrace nontraditional casting. The bass-baritone Simon Estes, “who has been outspoken about the struggles he and other black artists have faced in opera, considers the all-black cast stipulation a disservice both to Porgy and Bess, and the cause of integration.” Estes suggests that “music knows no color, and that it is unconstitutional for Porgy and Bess to be performed only by black artists. Porgy and Bess is a great opera, and no one should be barred by race from performing it onstage.” Casting the work with black artist does seem to assure authenticity, but the dramatic element of opera has never been based on that kind of reality. If we can accept the morbidly obese Luciano Pavarotti in the role of a starving Parisian poet, or Leontyne Price as the adolescent geisha in Madame Butterfly, is it such a far stretch to imagine Bryn Terfel as Porgy? A music critic recently wrote, “It is not that appearance does not matter in opera. But voice, artistry and dramatic presence matter more.”

Porgy and Bess is an American classic, and Gershwin clearly wanted the depiction of an African-American community in crisis to have authenticity. However, there have been growing calls that this opera should embrace nontraditional casting. The bass-baritone Simon Estes, “who has been outspoken about the struggles he and other black artists have faced in opera, considers the all-black cast stipulation a disservice both to Porgy and Bess, and the cause of integration.” Estes suggests that “music knows no color, and that it is unconstitutional for Porgy and Bess to be performed only by black artists. Porgy and Bess is a great opera, and no one should be barred by race from performing it onstage.” Casting the work with black artist does seem to assure authenticity, but the dramatic element of opera has never been based on that kind of reality. If we can accept the morbidly obese Luciano Pavarotti in the role of a starving Parisian poet, or Leontyne Price as the adolescent geisha in Madame Butterfly, is it such a far stretch to imagine Bryn Terfel as Porgy? A music critic recently wrote, “It is not that appearance does not matter in opera. But voice, artistry and dramatic presence matter more.”

George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess, “I got plenty o’nothing”