San Salvatore Theatre in Venice

On 7 November 1699 the San Salvatore Theatre in Venice produced the drama per musica “L’amar per virtù” (To love for the sake of virtue), with music attributed to Antonio Draghi. The plot focuses on the establishment of Moorish rule in Spain, and features the character of Egilda, who as the daughter of a North African army commander turns out to be the daughter of the last king of the Goths. Anna Maria Battaglia, a Bolognese singer employed by the Duke of Mantua, sang the role of Egilda.

Teatro Goldoni

However, the cast also included the 15-year old Margherita Raimondi (1683/84–1721), who was back on stage in December of the same year in the drama per musica “Il duello d’amore e di vendetta” (The duel of love and revenge) with music attributed to Marc Antonio Ziani. The last Gothic king to rule Spain seduces the young noblewoman Florinda with the promise of marriage. The future of Spain was thought to depend upon the son to whom Florinda gave birth. As you might rightly have guessed, Margherita Raimondi sang Florinda on stage, and Tomaso Albinoni quickly seduced her in in real life.

Tomaso Albinoni: Ardelinda, “Se avessi più d’un core”

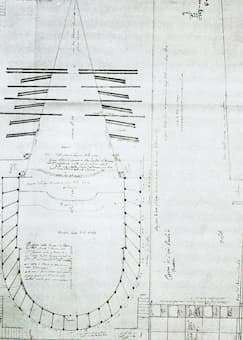

Fountain drawing of Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice

The Venetian composer Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1750) had introduced himself to the world of opera with Zenobia, first staged at the Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice in 1694. Tomaso surely met Margherita within this operatic environment, but details of the ensuing courtship can only be guessed at. We do know however, that Albinoni married Raimondi on 17 March 1705. The composer Antonino Biffi (1666-1732), a close personal friend of Albinoni, witnessed the happy occasion. Biffi was a singer in the choir of the Chapel of St. Mark’s Basilica, and in 1701 he applied for the position of maestro di cappella of San Marco. He was officially appointed in 1702, and held the office until his death. Tomaso and Margherita settled in the posh Venetian district of San Trovaso, and all together, the couple had three sons and four daughters.

Tomaso Albinoni: Zenobia Regina de Palmireni (exerpts)

West Facade of St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice, Metropolitan City of Venice,

Region of Veneto, Italy

Tomaso’s father Antonio Albinoni died in 1709, and he left one of his several shops to Tomaso, but the majority of his operation to his two younger sons. In the event, once the heirs started to examine the books they were surprised to find a mountain of debts to virtually wipe them all out financially. Tomaso now entered the ranks of the self-employed, and his best source of income appears to have been a singing school that he had opened previously. For the first time in his life, Albinoni had to generate income from his musical activities, and the couple was forced to relocate their residence into the less exclusive neighborhood of San Barnaba. Albinoni started to refer to himself as “Musico di violin” on the title pages of his printed works, and Margherita Albinoni continued her singing career and appeared in various productions after her marriage. For one reason or another, however, she did not perform in her husband’s operas. The singular exception was her appearance in “I rivali generosi,” staged in Brescia in 1715.

Tomaso Albinoni: Sonata da chiesa in D Minor, Op. 4, No. 1 (Ad Corda)

View of the Squero di San Trovaso, Venice

Focused on making money, Albinoni concentrated on instrumental music. He had enjoyed good success with his first collection of trio sonatas, but he now addressed a growing musical demand beyond the traditional homes of musical performance, court and church. A lively secular music scene was developing, “bolstered by professional musicians and a growing number of amateurs. Insatiable demand for new music fostered the development of new genres, amongst them the symphony and the instrumental concerto.” Music publishing was expanding rapidly, and advances in engraving and printing technique fostered steadily growing competition.

Church of San Barnaba in Venice

Albinoni’s music became known and valued well beyond Italian boarders, and that specifically applied to his concertante works for the oboe. Margherita, meanwhile, conquered Europe’s operatic stages and we find her performing in Torri’s “Lucio Vero,” in Munich in 1720. Sadly, Margherita developed health problems and unexpectedly died from a massive intestinal infection on 22 August 1721. Heartbroken, Tomaso found solace in composition, and he was invited to supervise and compose a number of works for the Electoral Court in Munich. He produced a flourish of operas, but as far as we know, Tomaso never remarried and eventually died in Venice in obscurity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Tomaso Albinoni: Filandro (excerpts) (Ann Hallenberg, mezzo-soprano; II Pomo d’Oro; Stefano Montanari, cond.)