Let’s continue to explore more contemporary Chinese music.

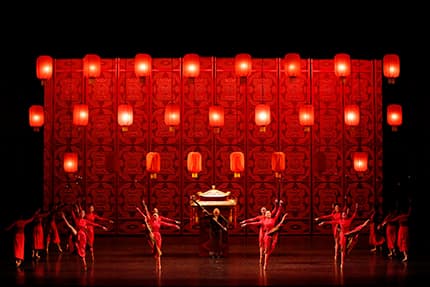

Raise the Red Lantern Ballet

Xu Zhenmin: “A Tone Picture of Border Village” (Shanghai Orchestra; Peng Cao, cond.)

The contemporary Chinese composer Xu Zhenmin uses a variety of modern compositional techniques while simultaneously imagining the unique color and charm of Chinese traditional music. He inherited a variety of traditional performing styles from Chinese classical music, and he has been active in promoting Chinese culture abroad. Well-versed in the seemingly endless streams of Western compositional techniques, Xu’s compositions are deeply grounded in the cultural identity and aesthetic value of the historical origins of Chinese culture poetry. His unique “Tone Picture of Border Village” takes us back to his cultural origins.

Five Flower Lake in Sichuan

In a conscious continuation of programmatic music, Chinese composers tend to rely heavily on folk songs for inspiration. Music is commonly associated with pictures, including idyllic landscapes. Huang Huwai composed his “Sichuan Suite” for piano in the 1950s. By incorporating local folk melodies, the composer draws attention to the beauty of the countryside and his own feelings of nostalgia.

Huang, Hu Wei : “Sichuan Suite” (Kwok Kuen Koo, piano)

Guo Wenjing

Born in the ancient city of Chongqing, located in China’s mountainous Sichuan province, Guo Wenjing was one of only a handful of students accepted at the Beijing Central Conservatory of Music when it re-opened in 1978. While many of his acclaimed colleagues, including Tan Dun, Chen Yi, and Zhou Long gradually made their home to the West, Guo remained in China after graduation. Guo’s music is filled with the spirit of humanism, and the New York Times praised him as the “only Chinese composer who has never lived abroad but established an international reputation.” As a composer, he explores the possibility and potential of combining Chinese art, Mandarin librettos, and Western opera to advocate both Chinese and Western approaches to timbre, melody, and harmony. As a critic wrote, he “oscillates between these styles and combines them with dazzling fluidity.” He composed Lotus (Lianhua) for the London 2012 Olympic Games. This magnificent composition explores the various cultural meanings and associations of this flower used to represent sacredness, resurrection, gracefulness, and a kind of ideal personality; “born in mud, but not stained; washed by clear ripples, but not coquettish.”

The composer writes, “Many early civilizations regard lotus as a holy symbol, and merge the image of the flower into their respective art and architecture. Lotus blossoms open and close following the sun, and in China, the cultural meaning of lotus is tied to an idealized and archetypal personality, beautifully described by the famous Neo-Confucian philosopher and cosmologist of the Song Dynasty, Zhou Dunyi.

Guo Wenjing: Lotus “Lianhua” (Overture)

Award winning composer and UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador Tan Dun has long probed the relationship between performer and audience by synthesizing Western classical music and Chinese ritual. “If we look at the idea of ‘art music’ with its firm separation of performer and audience,” Tan Dun writes, “we see that its history is comparatively short. Yet the history of music as an integral part of spiritual life, as ritual, as partnership in enjoyment and spirit, is as old as humanity itself.” Looking at the Western orchestra as a “dramatic medium and theater,” he combined cultural theatricality with spiritual ritual, resulting in his setting of Farewell My Concubine. It tells the tragic tale of the ancient beauty Consort Yu, who sacrifices herself rather than abandoning her king as he faces military defeat; cultures converge in the virtuosity of the piano and the energetic beauty and theatricality of Peking Opera. The original play tells the story of Xiang Yu, the self-styled “Hegemon-King of Western Chu” who battled for the unification of China with Liu Bang, the eventual founder of the Han Dynasty. In the play, Xiang Yu is surrounded by Liu Bang’s forces and on the verge of total defeat, so he calls forth his horse and begs it to run away for the sake of its own safety. The horse refuses, against his wishes. He then calls for the company of his favorite concubine, Consort Yu. Realizing the dire situation that has befallen them, she begs to die alongside her master, but he strongly refuses this wish. Afterwards, as he is distracted, Yu commits suicide with Xiang Yu’s sword.

Tan Dun: Farewell, My Concubine

For Tan Dun, who musically reimagined the original tale in symphonic terms, the piano is the most universal instrument in the world, and Peking Opera is China’s national opera, a universal art form. These two forms each carry musical and theatric elements from East and West, and the artistic and philosophical significance is very enticing. “I use the piano to portray King Xiang Yu,” Tan Dun explains, “and soprano to portray the ancient beauty Consort Yu.” The lyrical singing styles embody Consort Yu’s gentleness, beauty, kindness, and her love for family, country, and the world. In turn, the piano boldly showcases Xiang Yu’s unparalleled hero’s valiance and his willingness to die rather than give up his noble integrity. Unfolding in five continuous sections, this highly significant work creates an exciting synergy between traditional Chinese art forms, ranging from dance and music to the raw beauty of swordplay and martial arts. Critic Ken Smith has suggested “Tan’s score remains free of exoticism, its westernisations freely referencing Cage, Cowell and Crumb while the Chinese front extended traditional Peking opera technique, notably mimicking the clamour of Peking opera percussion and plucking piano strings like a Chinese zither.”

Ding Shande: Long March Symphony (Nagoya Philharmonic Orchestra; Kektjiang Lim, cond.)

Cultural and political history has provided amply inspiration for Chinese composers. Ding Shande, former Dean of the Composition Department and Vice-President of the Shanghai Conservatory, musically encoded an ideological manifesto commemorating the “Long March” of 1934/35. Evading the pursuit of the Kuomintang army, the Red Army of the Communist Party of China, under the eventual command of Mao Zedong, reportedly traveled over 9,000 kilometers in 370 days. The Long March left the Red Army on the brink of annihilation, but it sealed the personal prestige of Mao and his supporters for many decades to come. After collecting oral histories from soldiers who had actually taken part in the Long March, Ding Shande completed his tone poem in 1962. “Liu Yang River” comes from the 1950s opera “Submitting the Grain Tax” by Tang Bi-guang. Retaining the Hunanese folk characteristics of the melody, Wang Jian-zhong’s fashioned a delightful piano transcription in 1972.

Tang, Bi Guang: “Liu Yang River” (Jie Chen, piano)

Born in Beijing, composer Zhou Long is internationally recognized for creating a unique body of music that brings together the aesthetic concepts and musical elements of East and West. Deeply grounded in the entire spectrum of his Chinese heritage, including folk, philosophical, and spiritual ideals, he is a pioneer in transferring the idiomatic sounds and techniques of ancient Chinese musical traditions to modern Western instruments and ensembles. Winner of the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for his first opera, Madame White Snake, Zhou also received the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award from the Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society in 2012/13. Zhou composes in a variety of genres, and his works are widely performed and recorded. “The Rhyme of Taigu” dates from 2003 and attempts to revive a Chinese tradition of drumming that formed the basis of court music during the Tang dynasty. By drawing on both Chinese and Japanese traditional elements alongside a contemporary western orchestra ensemble, Zhou reimagines the energy and spirit of the original ceremony.

Zhou Long: “The Rhyme of Taigu”

The 1991 film Raise the Red Lantern, directed by Zhang Yimou and starring Gong Li, presented a clear departure from the propaganda films commonly associated with Chinese movie making. Li plays a student in northern China in the 1920’s who agrees to become the fourth wife of an ageing clan leader. Only 19, she finds herself confined to the old man’s palatial complex, where his other wives conspire with courtiers, and intrigue is permanently in the air. The red lantern of the title is hung outside the rooms of whichever wife the clan leader presently favours, and it soon becomes clear that the only way the youngest one can compete is to provide good sex and feign pregnancy. Since she is beautiful, her power soon increases, but she is not as innocent as we think. Nevertheless, the other wives’ intrigues and her descent into paranoia inevitably lead to tragedy. Viewed as a parable about the patriarchal, semi-feudal society of late 20th-century China, the film featured rich color and a claustrophobic atmosphere that perfectly matched the story. The film was later adapted into an acclaimed ballet of the same title by the National Ballet of China, directed by Zhang Jiping.

Zhao Jiping & Zhao Lin: Red Lantern for Pipa and String Quartet

Zhao Jiping

Zhao Jiping trained at the Xi’an Conservatory of Music, and majored in composition in 1970. He subsequently attended the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, and composed original music for the film. Internationally known as the composer for the “Fifth-Generation” filmmakers, including Chen Kaige, Zhang Yimou and He Ping, his most famous film scores are Raise the Red Lantern (1991), To Live (1993) and Farewell My Concubine (1993). Never straying far from his folk roots, Zhao Jiping’s music makes colorful use of Chinese instruments, such as the banhu, xun and sheng, and he uses them in combination with a Western orchestra. In his 2015 score Red Lantern for Pipa and String Quartet, his son Zhao Lin pays homage to his father’s famous film score. Inspired by Chinese traditional Beijing Opera, the work, according to the composer, “explores a unique musical style and language with the many colors of our traditional music.” The quintet is a suite of stories—unfolding in five movements titled Prelude – Moonlight, Wandering, Love, Death, and Epilogue—that takes place in a traditional Chinese private courtyard through the centuries. It tells an emotional story of Chinese family relationships in older times and the impact of the family’s isolation from society.

Liu Xuenan: Song of the Great Wall (Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra; Kenneth Jean, cond.)

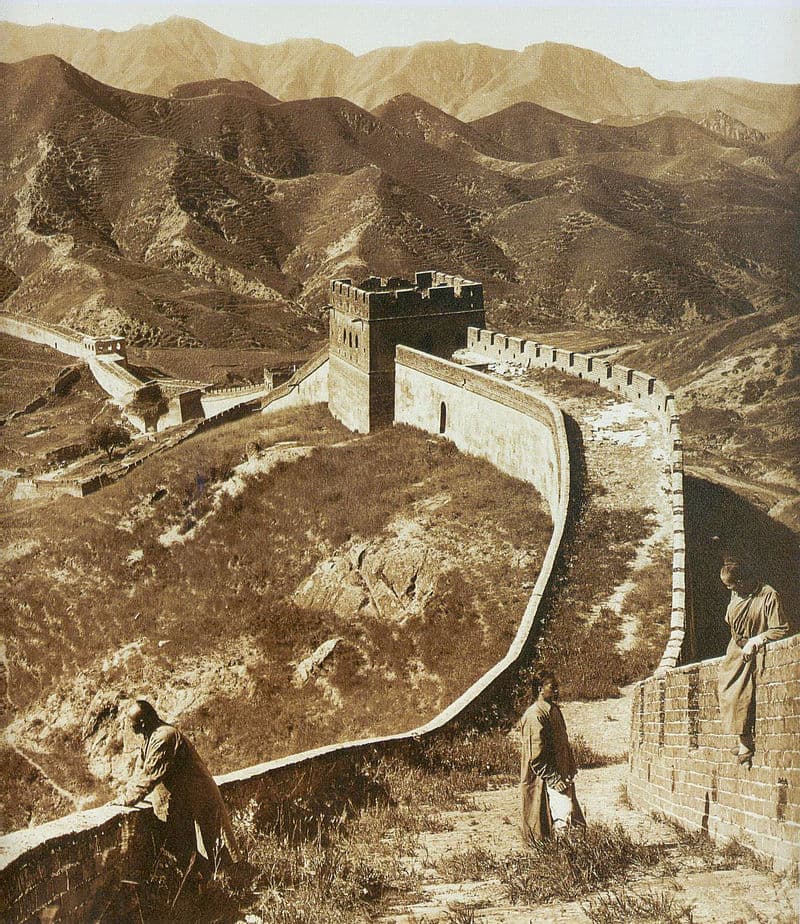

Great Wall of China in 1907

The Great Wall of China, a series of fortifications built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China, is a source of continued wonder. The Great Wall boasts a history of over 2,000 years and it stretches more than 3,000 miles across several provinces of northern China, making it one of the most impressive ancient structures on the planet. It is a remarkable feat of construction and engineering and a symbol of national pride. In his “Song of the Great Wall,” composer Liu Xuenan also sees the structure as a symbol of sacrifice, nostalgia, and sadness. Countless men were conscripted for this massive building project, and they were forever separated from their families. Originally written by Yan-Jun Hua, “Reflection of the Moon in the Er-Quan Spring” is regarded as the best composition ever for the Erhu, an ancient two-stringed instrument. Yan-Jun Hua was an itinerant street musician known as “Blind Bing.” His song features a lyrical, fluent, and flowing melody, but under its gentle surface, we can hear the strength and depth of the stubborn and blind composer. The tune has been called the Chinese version of Barber’s “Adagio,” and it can be heard in countless arrangements, such as in this string quartet version based on a string orchestra version fashioned by the famous Chinese composer Zu-Quiang Wu.

Hua Yan Jun: Reflection of the Moon in the Er-Quan Spring (Shanghai Quartet)

Zhou Jiaojiao with musicians

For countless centuries, Chinese philosophy has combined the Confucian five virtues and the five Taoist elements of nature in different ways. Yet, the five virtues and five elements provide ultimate powers only when they are fully combined as one. In the uniquely theatrical symphonic poem “Ode to Nature,” Zhou Jiaojiao tells the story of Blossom, a beautiful and talented girl with a bright future. She has a great gift for dancing and for playing the Chinese single-string lute, but tragedy strikes without warning. At the age of 17, Blossom is diagnosed with bone cancer, and in order to save her life, she has to undergo an amputation. “Ode to Nature” is all about the transformation of the human spirit, and about Blossom’s power over her life. By combining the five virtues and five elements she finds light amidst darkness and victory in defeat. The composer relates, “I wanted to present the concepts of Chinese classical philosophy to international audiences, which on first glance might seem boring and irrelevant…This journey into art and music can possibly even reflect universal truths.”

Zhou, Jiaojiao: Ode to Nature (Christiana McMullen, soprano; Jovahnna Borboa, soprano; Matthew Plenk, tenor; Matthew Peterson, baritone; Will Barksdale, baritone; Yimin Miao, dizi; Ying Lei, duxianqin; Hui Liu, gu-zheng; Xiaoxia Zhao, guqin; Fanhe Liu, pipa; Tao Jin, bells; Ian Wisekal, oboe; Susan McCullough, horn; Puiying Wong, violin; Katharine Knight, cello; Ann Marie Liss, harp; Howard Fang, electric guitar; Lamont Symphony Orchestra; Lawrence Golan, cond.)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter