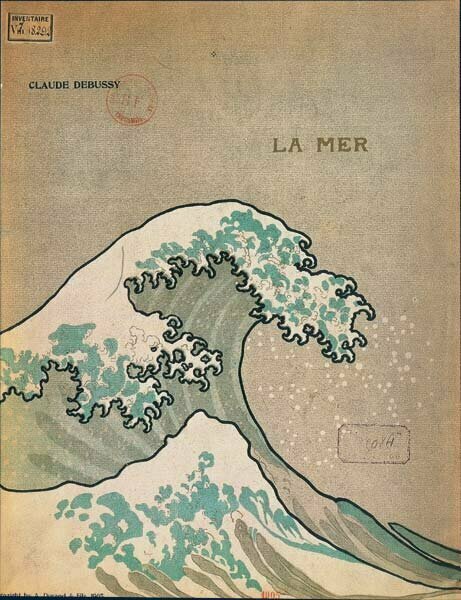

Ukiyo-e Japanese woodblock prints “The Great Wave off Kanagawa”

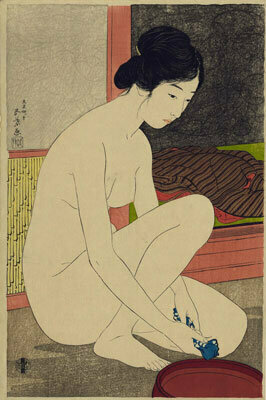

The Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) is best known as the author of a woodblock print series entitled “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.” That series contains probably the most iconic print image associated with Japan, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa.” Active during the Edo Period (1603-1868), Hokusai worked in a popular art form taking its name from combining “uki” for sadness and “yo” for life. “Ukiyo-e,” literally translated as “floating world pictures,” reflects the Buddhist concept of life as a transitory illusion.

Debussy’s La Mer

Ukiyo-e appealed to a broad spectrum of the Japanese public as the process of woodblock printing was capable of producing large quantities of prints that could be circulated at low cost. But more importantly, ukiyo-e artists developed a distinct polychromatic pictorial character for their art that frequently depicted idyllic narratives of nature, beauty, poetry, spirituality, love, and sex. And when Hokusai’s “Great Wave,” found its way to Europe and America, it stunningly appeared on the cover of Debussy’s La Mer of 1905.

Claude Debussy: La Mer (Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

“Black Ship”

The Edo period in Japan, ruled by the Tokugawa shogunate, was a peaceful era of economic growth, strict social order, popular enjoyment of arts and culture, and severe isolationist foreign policies. Having almost completely eradicated Christianity, a single trading port was established in Nagasaki with only China, the Dutch East India Company, and for a short period of time, the English, allowed to visit Japan for commercial purposes. Anybody else landing on Japanese shores was put to death without trial. And thus it was left to United States Naval Commander Matthew Perry to steam his “Black Ship” into the harbor of the little fishing village of Shimoda on the Izu Peninsula in 1853.

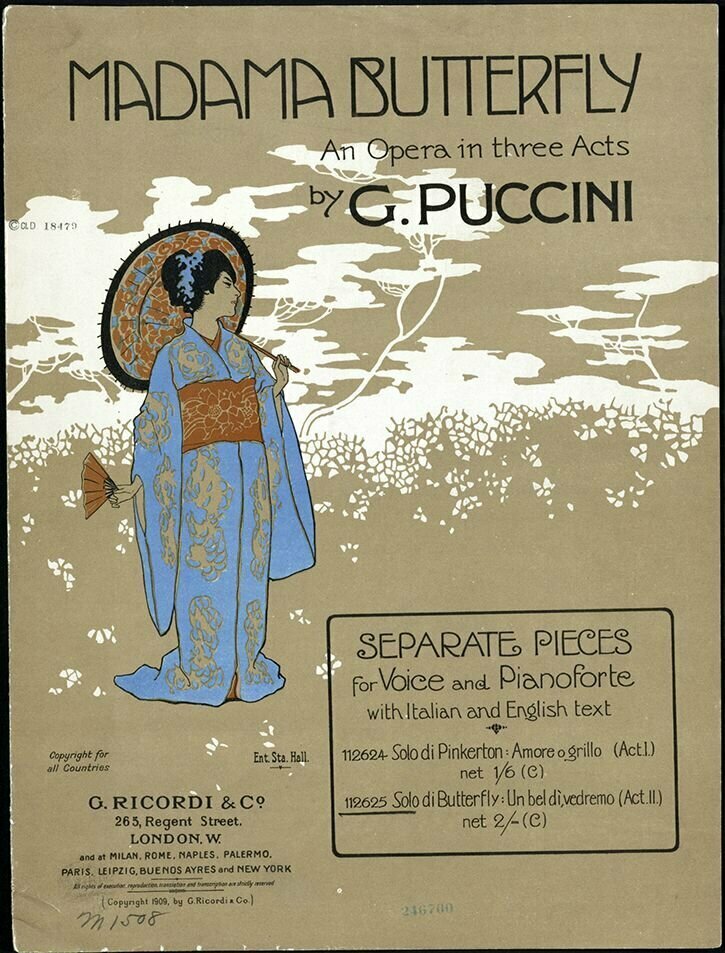

Madama Butterfly

In one of the most famous examples of “Gunboat Diplomacy,” Perry helped to negotiate an 1854 treaty with Japan that opened its doors to the West after nearly 200 years of cultural and political isolation. Western exposure to Japanese art and culture immediately became a significant stimulus, and as we all know, the fascination with these cultural differences lies at the core of Puccini’s operatic setting of Madama Butterfly.

Giacomo Puccini: Madama Butterfly, “Un bel di, vedremo”

Initially however, it was ukiyo-e that found its way into the Western world. A number of prints were shown at the Japanese Satsuma Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1867, and it quickly became fashionable in France and England.

Walter Niemann

The influence of this exposure, depending on context, became known as “Japonerie,” “Japonaiserie,” or “Japonisme.” And it was the aesthetics of the ukiyo-e style that would profoundly influence various Western artistic movements, including the visual artist Manet, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Whistler and numerous others. And the composer Walter Niemann wrote in 1912, “that as in fine art, Impressionism in music is fundamentally based on Japanese influences.” Niemann’s own set of character pieces entitled Japan illustrates according to the composer “a dream image that a German tone-poet had of Japan.”

Walter Niemann: Japan, Op. 89 (Noriko Ogawa, piano)

Igor Stravinsky

When Igor Stravinsky visited Japan in the spring of 1959, he told a reporter. “I came into contact with Japan in the course of my work many years ago. In 1913, I composed a small work, which used three short Japanese poems for its texts. I was attracted at the time by Japanese woodblock prints, a two-dimensional art without any sense of solidity. I discovered this two-dimensionality in some Russian translations of poetry, and attempted to express it in my music.” Respectively dedicated to the composers Maurice Delage—who had visited Japan in the spring of 1912—Florent Schmitt, and Maurice Ravel, Stravinsky set the “Tanka” texts in the Russian translations of A. Brandt. The titles of individual songs refer to the poets Akahito Yamanobe, Masazumi Miyamoto, and Tsurayuki Ki, and they encapsulate nature images associated with Japan, including “snow gently falling during spring, and the color of cherry blossoms seen on a distant mountain.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Igor Stravinsky: Three Japanese Lyrics (Jane Manning, soprano; The Nash Ensemble; Simon Rattle, cond.)

As usual, Georg Predota’s article is not only well written and interesting, but shows the very important connection between art and music. Well done!