“A thousand years of musical and cultural Identity”

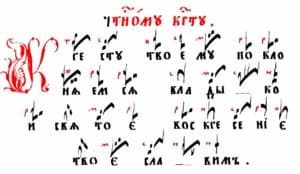

Ukrainian choral music Znamenny notation

Choral music has always held special significance in Ukrainian national culture. A good many features of what might be called an indigenous Ukrainian musical style formed and evolved from its choral music. “In the most fundamental way,” writes a scholar, “choral music embodies Ukrainian national mentality, and the soul of the people.”

With ever-changing borders and territories, Ukraine became a truly independent state only in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Yet choral art in the Ukrainian lands stretches back for over 1,000 years. The so-called “Znamenny Chant” stood at the core of Eastern Byzantium church music and rites, but a good number of the early sources have not been fully deciphered to date. Eventually, responding to Western European developments, notation was reformed by the Kyiv square notation. “It was then that Ukrainian choral culture finally came out of its imperial shadows, and in full voice declared to the world its originality, uniqueness and accomplishments, and its achievements, distinctiveness and self-identification.”

Mykola Dyletsky: “Herouvimska” (Song of the Angel) (Svetoslav Obretenov National Philharmonic Choir; Georgi Robev, cond.)

Mykola Dyletsky’s theoretical music treatise

The most famous Ukrainian composer in the 17th century was the music theorist, composer, and pedagogue Mykola Dyletsky (1650?-1723?). He received a Jesuit education in Vilnius, and worked in Smolensk, Kyiv, Moscow, St Petersburg, Lviv, and Cracow. As a theorist, his most important work is titled “Musical Grammar,” and it explains the fundamental theory of music, counterpoint, and the general rules of composition. “His theoretical views are augmented by comments on esthetics and on the educational value of music.”

As such, Dyletsky is celebrated as the author of the first theoretical music treatise in Eastern Europe, and his work exists in several edited versions and languages. As a composer, Dyletsky is considered a master of polyphonic and polychoral music. He composed a number of works that includes a liturgy for four voices, and two for eight voices, alongside four-and eight voice polychoral concerts. “The Ukrainian Baroque polychoral concerto rightfully occupies a significant place not only in the Ukrainian national musical culture but also in European musical history, where it represents a significant step towards the formation of a new European musical culture.” But what is more, the Syrian Archdeacon Paul of Aleppo reported while traveling in Ukraine, “The singing of Cossacks gladdens the soul and heals it from longing because their singing is pleasing. It comes from the heart.”

Maksym Berezovsky: Eucharistic Verses (Chamber Choir of the Ukrainian Music Vidrogennia; Mstislav Yurchenko, cond.)

Maksym Berezovsky’s choral concerto Ne otverzhy mene

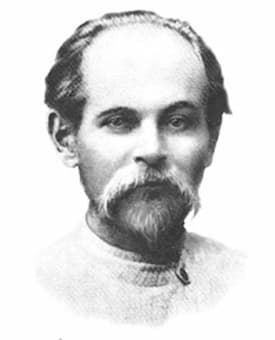

Maksym Berezovsky (1745-1777), one of the most outstanding Ukrainian composers of the 18th century, incorporated all the leading genres of Western European music into his compositions. He traveled to Italy to study with the famed Padre Martini in Bologna, and he was elected to the Bologna Philharmonic Academy, receiving the title of “Academy Composer.” His opera Demofonte was staged in Italy in 1773, and the sonata for violin and harpsichord dates from that period as well.

Maksym Berezovsky

A recently discovered symphony is “the first symphonic work written by a composer from the Russian Empire, and it is probable that a considerable number of his other instrumental compositions have been lost.” He also composed a series of sacred works, including 12 sacred concertos and a full cycle of liturgical chants. Details are still sketchy, but once Berezovsky had returned to St Petersburg in 1775, he “committed suicide as the result of court intrigues and difficult circumstances.” Berezovsky’s musical legacy is striking for its exceptional originality, “the boldness of his creative quest, and its clarity of form and strength of expression.” Scholars rightfully suggest that his compositions “should be ranked alongside that of the most distinguished masters of his era.”

Dmytro Bortniansky: Sacred Concerto No. 27, “With my voice unto the Lord have I cried” (Ensemble Cherubim; Marika Kuzma, cond.)

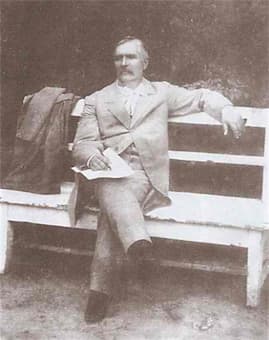

Dmitry Bortniansky, 1810s

Dmitry Bortniansky (1751-1825) was born in Hlukhiv, Ukraine, and grew up singing in the choir of the Russian Imperial court. Between 1769 and 1779 Bortniansky studied in Italy, where he composed several operas to Italian librettos: Creonte (1776) and Alcides (1778), staged in Venice, and Quinto Fabio (1779), staged in Modena. On his return to St Petersburg he became the first native Slavic Kapellmeister to the Czars. He composed a number of French operas, and wrote instrumental music, including piano sonatas and a piano quintet with harp. When he became director of the court choir in 1796 he performed “not only his music and that of his contemporaries in St Petersburg but also Handel’s Messiah, Haydn’s Creation, and, most notably, the world première of Beethoven’s Missa solemnis.”

Dmitry Bortniansky monument in Hlukhiv

During this particular period Bortniansky composed over 100 choral religious works, including 35 concertos for four-part mixed choir, 10 concertos for double choruses, 14 panegyric hymns, and a number of liturgical works for three and four voices and for double choruses. With a highly versatile and professional choir at his disposal, Bortniansky was able “to incorporate a symphonic approach to the a-capella choral medium.” His music is at once intimate and magnificently expressive, and when Hector Berlioz heard Bortniansky’s music during his travels to Russia, he heard “an entanglement of voice parts that seemed impossible: vague murmurs as one sometimes hears in dreams and attacks that, in their intensity, resembled outbursts, seizing the heart all of the sudden.”

Mykhailo Verbytsky: “National Anthem of Ukraine”

Mykhailo Verbytsky

Every Nation needs a national anthem, and the music for the Ukrainian National Anthem, which is rightfully heard frequently these days, was composed by Mykhailo Verbytsky (1815-1870). Vebytsky was a Catholic priest who studied in the Peremyshl Cathedral Music School with A. Nanke and later took private lessons with F. Lorenz. Peremyshl became a center for choral music in search of a national Ukrainian identity.

As a choral music composer, Verbytsky was strongly influenced by Bortniansky, and he composed a number of works for mixed and male choir and countless religious hymns. He also wrote music for theatrical performances and “completed incidental music for 18 plays, operettas, and vaudevilles. He wrote several symphonies, but most of them remain unfinished.” His choral music greatly inspired subsequent generations of composers, including Ivan Lavrivsky, Victor Matiuk, Anatole Vakhnianyn, Isidor Vorobkevich, Ostap Nyzhankivsky, Vasyl Barvinsky, Stanislav Lyudkevych, Anatoly Kos-Anatolsky, and Yevhen Kozak. However, Yerbytsky is best known for composing the Ukrainian national anthem “Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished,” to a text by Pavlo Chubynsky, in 1862. Maybe President Putin should have taken the time to actually understand the meaning of that anthem before launching his inhuman war against a sovereign and internationally recognized country.

Mykola Lysenko: “Bozje welyky” (Utrechts Byzantijns Koor; Grigori S. Sarolea, cond.)

Mykola Lysenko, 1865

In a previous episode we have described Mykola Lysenko (1842-1912) as the father of Ukrainian music. Significantly, Lysenko found the musical and cultural source of Ukrainian identity in ethnographic projects that involved collecting, transcribing, recording, and publishing a substantial number of folksongs. He arranged roughly 500 folk songs, including both solos and choruses with piano accompaniment, and a-capella choruses, during his lifetime. Lysenko focused on the tonal and harmonic characteristics of Ukrainian folk songs, and “fashioned arrangement of various types of songs based on a specific Ukrainian cultural tradition.”

Mykola Lysenko in Kyiv

In fact, Lysenko was adamant to clearly demonstrate the differences between the folk music of the Ukraine and that of Russia. The choral compositions by Lysenko are primarily secular, with works in different genres based on texts by the Ukrainian National poet Taras Shevchenko and other Ukrainian writers. By contrast, his religious choral output is comparatively small, but we do find the famous Prayer for Ukraine, “which became a national church hymn of Ukraine.” Lysenko’s music features flowing Ukrainian melodies placed within a full choral texture. He paid particular attention to intonation, and his expressions of a distinct national Ukrainian musical style is lavishly clothed in the language of European Romanticism.

Kyrylo Stetsenko: “Millist Spokoyou” (Halina Zykrata, soprano; Alla Horobtchenko, alto; Fedir Potapchouk, tenor; Igor Babytch, bass; Anatolyj Hlalzyrin, bass; Wolodymyr Hritsiouk, bass; Ukraine National Academic Choir, “Dumka”; Evhenyj Savtchouk, cond.)

Kyrylo Stetsenko, 1910s

Following in the footsteps of Mykola Lysenko, Kyrylo Stetsenko (1882-1922) became one of his most brilliant successors in the field of choral music. Born in Kyiv province, he was educated in a theological seminary and joined a choir organized by Lysenko himself. After graduating in 1903, Lysenko began teaching music at the Kyiv pedagogical institute and he conducted church and secular choirs. He studied composition under “Hryhorii Liubomyrsky at the Lysenko Music and Drama School, and participated with leading Ukrainian musical figures in an unsuccessful attempt to establish an independent music publishing house.”

While he was compiling the songbook “Echo,” he was arrested for sedition and exiled to a town in the Donbas. He was ordained as a pastor in 1911, but ceased virtually all creative work until 1917. Eventually, he was recruited to the music department of the Ukrainian National Republic Ministry of Education and established a number of major Ukrainian choirs and choral societies. Unsurprisingly, he fell out of favor with the new Soviet authorities in 1920. “Stetsenko’s compositions and pedagogical work continued the Ukrainian national music tradition established by Lysenko.” Stetsenko composed in a variety of genres, and his compositions for choir are diverse in form, featuring religious works, cantatas, choral works both a-cappella and with piano accompaniment, and arrangements of Ukrainian folk songs, including carols.

Mykola Leontovych: “Carol of the Bells”

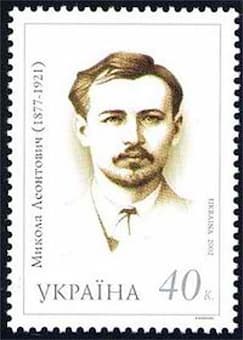

Mykola Leontovych

Mykola Leontovych (1877-1921) is one of the best-known Ukrainian composers of the twentieth century. His famous “Shchedryk” (Carol of the Bells) is still heard with some frequency around Christmas time in many countries. Born in southwest Ukraine he received his education in a Theological Seminary, but eventually decided against becoming a priest. Instead, he focused his energies on providing music education at various schools. He also worked with a number of choirs, and collected and arranged Ukrainian folk songs. Leontovych privately studied counterpoint in St. Petersburg, yet “in spite of the popularity of his compositions, he was modest about his work and remained a generally unrecognized figure until he was brought to Kyiv in 1918-19 to teach at Kyiv Conservatory and the Lysenko Music and Drama Institute.” His musical legacy consists of over 50 compositions for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, choral miniature based on melodies taken from folk songs, and four choral poems on texts by Ukrainian poets. The life of an educator and composer, as we have once again clearly seen in the last couple of weeks, can be incredibly dangerous. While Leontovych was working on his opera “For the Water Nymph’s Easter Sunday,” he was assassinated by an agent of the Soviet political police.

Lesia Dychko: “Vesnyanka”

Mykola Leontovych, late 1910s

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and a horrendous civil war, “the holdomor—murderous famines organised by the Communists—and the implementation of strict ideological dictates, the state of choral culture in Ukraine became distorted.” Professional composers were no longer allowed to work in the traditional national genre of church music. Instead, the State encouraged ideologically correct pieces on Party and Soviet themes and mass revolutionary songs. For over seventy years of Soviet totalitarianism, choral music entered a period of stagnation in Ukraine. However, as musicologist have explained, “the development of national choral music did not come to a complete end, but rather, it became distorted by slipping into arranging folk songs and into a process of folklorizing.”

Lesia Dychko

Nevertheless, the tradition of high professionalism continued in the choral artistry of Boris Lyatoshynsky and his successors Silvestorv, Stankovich, Skoryk, and Lesia Dychko. Born in Kyiv, Dychko eventually took up a position as professor at the National Musical Academy of Ukraine, teaching composition and music theory. Her compositions are based on Ukrainian folklore and the music of the Baroque. “After nearly a century of communist ban on church music, Dychko was the first modern Ukrainian composer to compose a liturgy.

Yehen Stankovych: “Requiem for those who died of famine”

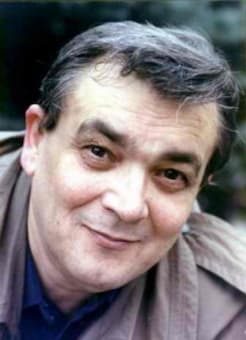

Yevhen Stankovych

Yevhen Stankovych studied at the Lviv Conservatory under Adam Soltys before transferring to the Kyiv Conservatory where he studied under Borys Liatoshynsky and Myroslav Skoryk and he graduated in composition in 1970. He worked as an editor at the “Muzychna Ukraina” publishing house in 1970–6. A recipient of the Shevchenko Prize in 1977, he has been a full member of the National Ukrainian Academy of Arts since 1997. One of the most prolific contemporary Ukrainian composers, Stankovych has written six symphonies and several symphonic works, three violin concertos as well as concertos for violoncello and orchestra, viola and orchestra, and flute and orchestra, and eight symphonies for chamber orchestra. In his choral works he turns to religious texts and genres, and takes his inspiration from Bach and Ukrainian composers of the Classical era, “creating dark colored, dynamic compositions.”

Iryna Aleksiychuk

A new generation of Ukrainian composers is eagerly embracing the millennia-old tradition of Ukrainian choral art. Among them is Iryna Aleksiychuk, a graduate from the Kyiv Tchaikovsky Conservatory, now the Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine. She is the winner of numerous prizes in composition, and in the 1st All-Ukrainian Composers’ Competition in Kyiv in 2001, her “Spiritual Psalms” received the award for best choral composition based on Biblical texts. In 2000, she was awarded the Levko Revutsky National Prize for her concert activity and performance of modern music.

Since 1994 Ms. Aleksiychuk has served as a professor of composition, orchestration, and score reading at the Tchaikovsky National Music Academy in Kyiv, and she maintains a busy performance schedule with concerts in Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, Moldova, Serbia, Italy, Germany, and the United States as a pianist, composer, and organist. In this time of renewed hostilities against Ukraine, I can’t think of a more touching tribute to the suffering of innocent people than her setting of Psalm 142.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Iryna Aleksiychuk: “My voice to the Lord”