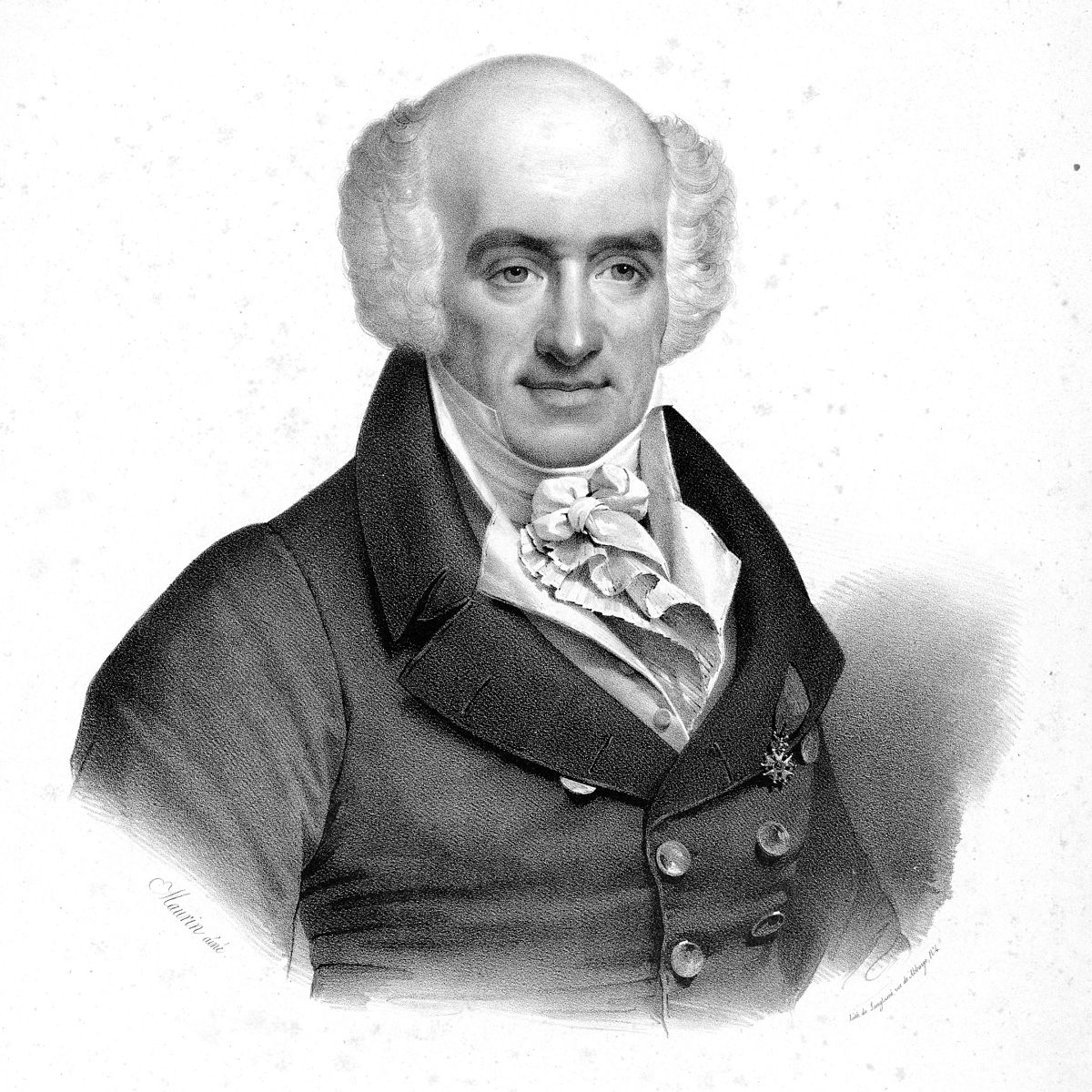

Charles-Auguste de Bériot

Credit: http://mblogthumb4.phinf.naver.net/

Pierre Rode: Violin Concerto No. 7 in A Minor, Op. 9

Napoleonic France had annexed the Benelux and chunks of Italy, facilitating the journeys to Paris of two Belgian child prodigies, Bériot and Massart, joint promoters of the Franco-Belgian violin school, which would unleash the greatest concentration of virtuosos ever seen.

In 1810, Charles-Auguste de Bériot (1802-1870), a violinist and pianist from Leuven, studied with Tiby. By age 20, he was performing widely on the violin, and even braved Qing Dynasty imperial interdicts to make a piano tour of China (his pianist son, Charles-Wilfrid, taught Ravel).

Turning down an offer of professorship in Paris – then given to Massart – he repatriated himself to the Brussels Conservatoire in 1843.

Bériot, Scène de Ballet Op.100

Itzhak Perlman

Henri Vieuxtemps

Credit: http://www.nndb.com/

Vieuxtemps later helped perfect the already affirmed talent of Liège-born Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931), admired by ageing 19th century masters, and looked up to by aspiring future stars, nicknamed “the King” and “the Tsar”, he set the professional standard for perfect intonation.

Fortunately, recorded evidence of his interpretations survives, displaying the clear structural analysis and technical mastery characteristic of the Franco-Belgian style.

Eugène Ysaÿe plays Vieuxtemps Rondino (1912)

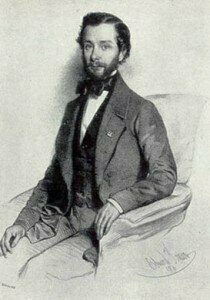

Lambert Massart

Credit: Wikipedia

In 1823, Lambert Massart (1811-1892) was sponsored by the Dutch monarch (now ruling Belgium) to study in Paris with Kreutzer. There – still only 14 – he developed the technique and aesthetic of sustained vibrato which won him the plaudits and friendship of Liszt and Berlioz, and guaranteed his pupils the best chances of a coveted First Prize: in fact, he achieved an all-time record of 52 Firsts in 63 years of teaching, beginning in 1828 when he was only 17 – his Belgian pupil Artôt only 13!

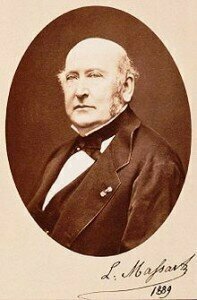

Henryk Wieniawski

Credit:

Wikipedia

Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) at 11, was Massart’s second and youngest First Prize pupil, a champion of vibrato and one of the most influential teachers of his generation. He furthered the development of the Russian violin school begun by Vieuxtemps who, on retirement, then entrusted him with his classes at the Brussels Conservatoire. He shared with Vieuxtemps the rewarding mission of completing Ysaÿe’s musical training.

Wieniawski – Variations on an Original Theme Op15

Fritz Kreisler

Credit: https://i.ytimg.com/

Crucially, as always, commercial incentive played a role, and the public’s enthusiasm for this novelty – still only available in live concerts during the pre-radio/pre-recording era – finally won the argument. As Massart approached retirement in 1890, students petitioned to ensure his vibrato technique would be supported by the next generation of professors. Predictably, within a few years, his prize-winning pupils occupied most titular posts.

Massart’s 1883 First Prize pupil, Albert Geloso, founded the Geloso Quartet, with Conservatoire colleagues Lucien Capet on 2nd violin and Pierre Monteux on viola. Lucien Capet went on to regenerate violin playing through his hugely influential “Superior Bowing Technique” (1916), while Monteux gained universal respect as one of the greatest interpreters of the orchestral repertoire.

Nevertheless, by all contemporary accounts, it was Massart’s 1887 First Prize pupil from Vienna, Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962) who best conveyed his teacher’s expressive qualities in performance. Numerous pre-War recordings testify to his refinement of tone, phrasing and vibrato.

Fritz Kreisler plays Thais-Meditation 1928

By his length of tenure, his development and his defence of sustained vibrato, and the sheer number of his extraordinary pupils, Massart was obviously the heavyweight of the Franco-Belgian school.

Intensely admired during his lifetime, he lived prosperously without needing to publish much, other than useful fingerings and bowings to his teacher Kreutzer’s Etudes. However, having left no methodological system nor memorable pieces to keep his name on music stands, his existence has been largely forgotten, even by specialist commentators – who should know better!

Those who claim that distinctions between the different violin schools have become blurred, are failing to admit how widely Franco-Belgian style has been adopted.

Let’s hope the recent recognition of Lucien Capet’s fruitful insights will inspire at least a respectful thought for his great predecessor, Lambert Massart.