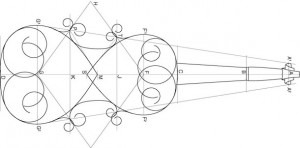

Underlying geometry of a violin design

Experimentation with violin design has occurred in every century – the basic body design of a violin was based on that of the already-extant guitar. And then the curly corners were added to make the violin we know today.

Luthiers, however, continued to experiment. What if we angled the violin body so that it was easier to play?

Neolin

What if we wanted a violin that your neighbors wouldn’t complain about at 3 in the morning? Then just reduce the violin to a frame and you have a practice violin

Practice violin

Also known as mute violins, these instruments keep the proportion of the original but remove all the elements that might make a sound.

Mute Violin

What if you were a working musician travelling on the road and needed a viable fiddle at the end of your journey but couldn’t take along a lot of luggage? In the day of the dancing master, he might carry a kit violin – a violin small enough to fit into a pocket. This was also known as the piccolo violin (the very small violin)

Kit violin

One composer who specified the use of the piccolo violin was J.S. Bach in his first Brandenburg concerto.

J.S. Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F Major, BWV 1046: IV. Minuet. (Matthew Jennejohn, oboe; Louis-Philippe Marsolais, horn; Olivier Brault, piccolo violin; Ensemble Caprice)

In remote places where fine luthiers were rare, it was not unknown for local craftsmen to make bowed instruments of a rudimentary nature, such as the box violin. The basis for the body, as is apparent, would be a box. The obvious problem with this instrument is that it lacks the waist that the regular violin has to aid the angling the bow correctly but that could be solved by angling the instrument itself instead of the box.

Box violin

When you get to the electric era, and add into that the availability of plastic and other new materials, your imagination is the limit! While Ted Brewer’s Vivo 2 Electric violin still has some ties to the regular violin, the Viper Electric violin seems to be far more innovative in its design.

Ted Brewer’s Vivo 2 Electric violin

Viper Electric violin

And very funny take on the uses and abuses of an electric violin