The famed Irish playwright, critic, and political activist George Bernard Shaw sent a personal letter to Jascha Heifetz after hearing a performance. He writes, “Your recital has filled me and my wife with anxiety. If you provoke a jealous God by playing with such super-human perfection, you will die young. I earnestly advise you to play something badly every night before going to bed instead of saying your prayers. No mortal should presume to play faultlessly.”

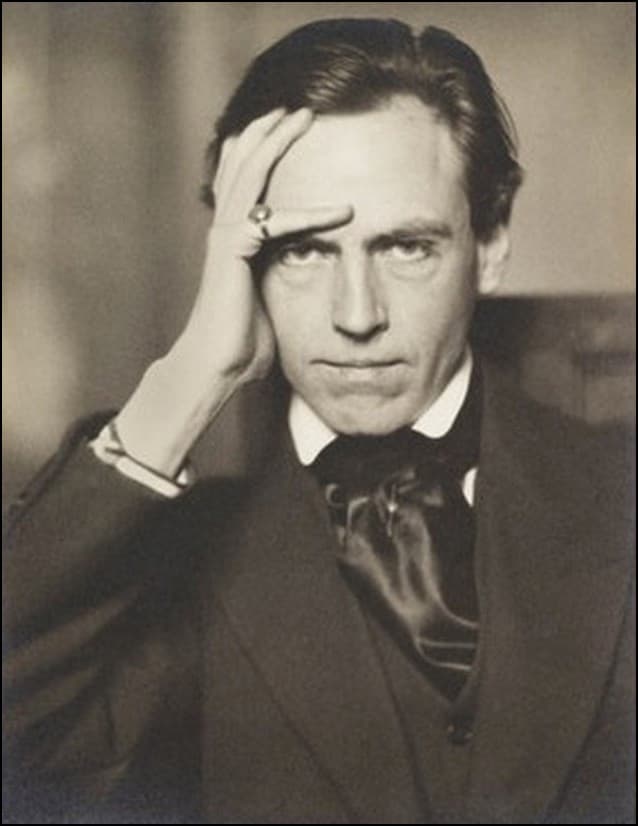

Jascha Heifetz

While the violinist’s flawless technique stands at the core of Shaw’s observation, the critic also seems to draw attention to Heifetz being frequently accused of being “cold and unemotional,” one might even say arrogant, on stage. To be sure, Heifetz’s playing posture was very erect, and he performed with little body movement or facial expression. Contrary to outer appearance, however, Heifetz described his stage presence as being “rather turbulent, underneath, and hidden…. An artist requires the nerves of a bullfighter, the vitality of a night-club hostess, and the concentration of a Buddhist monk.” Stage mannerisms aside, Heifetz raised the level of violin playing to previously unimaginable heights, and in a sense, he freed composers to write compositions at any technical level. Heifetz stimulated a good many musicians and composers, and we have decided to explore some of the violin masterworks inspired by one of the greatest violinists of all time.

Joseph Achron: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 1, Op. 60

Joseph Achron: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 1, Op. 60 (Elmar Oliveira, violin; Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra; Joseph Silverstein, cond.)

Joseph Achron

The composer and violinist Joseph Achron (1886-1943) originally hailed from Lithuania. His younger brother Isidore was an accomplished pianist who later became Jascha Heifetz’ accompanist in America. Joseph was a child prodigy who began violin lessons at the age of five and he composed a lullaby for violin at the age of seven. When his family relocated to St. Petersburg in 1898, Achron entered the conservatory and joined the class of legendary violin teacher Leopold Auer, whose other students included Jascha Heiftez, Mischa Elman, Efrem Zimbalist, Nathan Milstein, and Tascha Seidl. He studied composition with Anatoly Lyadov, and quickly penned a dozen compositions. Achron spent three years touring Germany, but he became increasingly interested in composition once he returned to St. Petersburg. As he was looking to become part of the general musical mainstream in Russia, he became attracted to the work and mission of the “Society for Jewish Folk Music.” This organization, counting musicians, ethnologists, folklorists, and intellectuals among its members, “attempted to establish a new Jewish national art music based on ethnic, as well as religious heritage.” His first composition after joining the organization was his “Hebrew Melody” for violin and piano, based on a theme he remembered hearing in a Warsaw synagogue in his youth. It remains his most famous piece, “and part of the standard repertoire of virtually all concert violinists, and a frequent encore number.”

Joseph Achron in Petersburg

Achron sought to develop a “Jewish harmonic and contrapuntal idiom that would be more appropriate to Jewish melodies than typical Western techniques, but he opposed the notion of an artificially superimposed Jewish style.” He was convinced that any possible stylistic development of Jewish national art music requires an evolutionary course, as he wrote in an essay, “any serious Jewish art music must be developed by gradual assimilation.” Achron rejected as naïve and chauvinistic the ideas of purity and authenticity, arguing that such purity does and cannot exist. “This is true of art as of life’s other constituents since inter-influences are not only unavoidable but desirable.” The Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 1, Op. 60 was Achron’s first large-scale work following his immigration to the United States. “It is also the first known concerto, for any instrument, with a movement based entirely upon the actual musical substance of authentic biblical cantillation.” The work is dedicated to his colleague, good friend, and enthusiastic supporter Jascha Heifetz, and it premiered in 1927 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Serge Koussevitsky and Joseph Achron as the soloist.

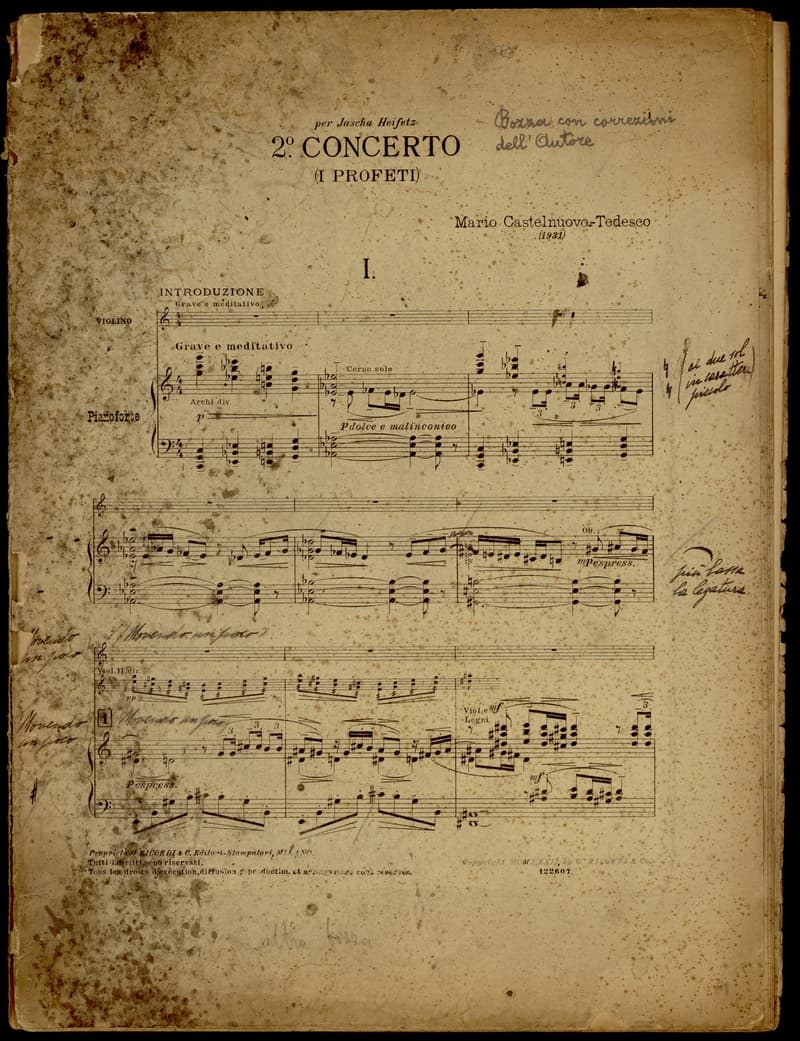

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2, Op. 66

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2, Op. 66 (The Prophets) (Jascha Heifetz, violin; Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Alfred Wallenstein, cond.)

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968) described his Concerto Italiano as “his first truly symphonic venture.” It was written for the violinist Mario Corti, and Castelnuovo-Tedesco decided to reach back to the lyrical style of violin playing in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It is a tuneful and transparently scored work that was, not always positively, described as “almost Vivaldian.” The work first publically sounded in January 1926, and one year later Castelnuovo-Tedesco met Jascha Heifez. The composer later wrote, “I owe to the “Concerto Italiano” the precious friendship of Jascha Heifetz. I met and heard him for the first time in Florence in 1926. He was very kind, told me that he knew my music from another eminent violinist, and asked me to send him my concerto. Naturally, I did so at once, but I must confess that I was a bit skeptical. I couldn’t hope that such a great violinist of world reputation might be interested in the work of a young, yet unknown composer. Well, I was mistaken. A year later I received a program from New York in which he had played my concerto.” That concert at the Metropolitan Opera House was a huge success, and Heifetz subsequently requested a concerto for himself.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Violin Concerto No. 2

Castelnuovo-Tedesco composed the Heifetz commission under the influence of “deep religious sentiment.” In fact, he produced a work of “biblical character and inspiration, using five traditional Jewish melodies,” which he discovered in an 1891 collection published by the violinist Federico Consolo. At first, Castelnuovo-Tedesco titled his Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2, Op. 66 “Isaiah, Jeremiah and Elijah,” but in the end he settled for the general title “The Prophets.” The work is cast in three movements and includes a substantial cadenza in the first. A central movement in traditional ternary song form eventually gives way to a happy dance melody in the Finale. Heifetz, Toscanini and the Philharmonic Symphony gave the premiere performance in Carnegie Hall on 13 April 1933. Reviews were mixed, with some praising the concerto’s tunefulness while others, like Olin Downes of the New York Times, dismissed it as “second-rate music.” Heifetz declared that he liked the concerto very much, but ruefully added, “no one else did.”

Miklós Rózsa: Violin Concerto, Op. 24

Miklós Rózsa: Violin Concerto, Op. 24 (Jascha Heifetz, violin; Dallas Symphony Orchestra; Walter Hendl, cond.)

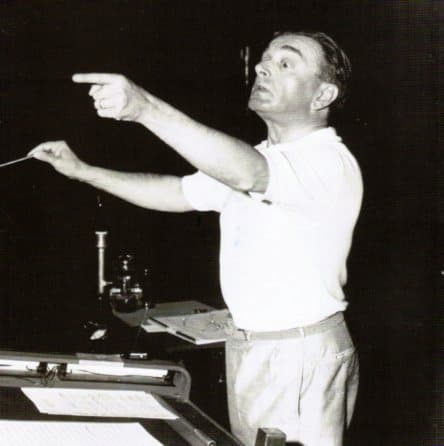

Miklós Rózsa

When it came to accepting and performing works dedicated to him, Jascha Heifetz was highly selective. He refused to play Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto in 1936, and rejected the Arnold Bax Violin Concerto in 1938. As such, Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995) approached Heifetz with a great deal of trepidation. As he later wrote, “As all great composers had written their concertos with a particular artist in mind, I wanted to do the same and decided to approach Jascha Heifetz. I had met Heifetz briefly once only… but did know his accompanist Emmanuel Bay. I asked him to approach Heifetz on my behalf. Heifetz sent back an answer that he was interested and suggested I write one movement which we could try through together before he made up his mind. This sounded rather risky to me. Heifetz had approved the first few pages of Schoenberg’s concerto, only to refuse to play the piece when it was finished—in fact, a number of concertos had suffered the same fate. It was a chance, but I decided to take it… He said he liked the piece, but there were certain cuts and changes he wanted to propose. Would I be willing to work with him on that? I was willing, of course. It is quite usual for a soloist to advise a composer in a situation like this. We worked at intervals over a period of months.”

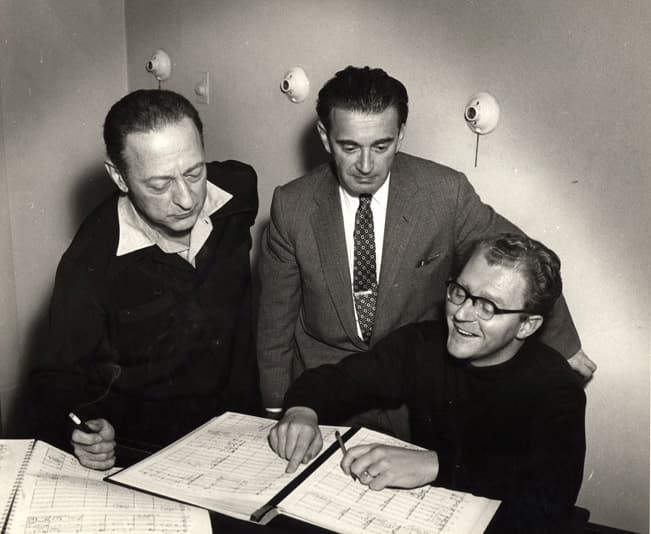

Miklós Rózsa, Jascha Heifetz and Walter Hendl

Rózsa remembers, “The premiere was given on 15 January 1956 in Dallas, Texas, with Walter Hendl as conductor. Heifetz played like a god. His tone was unsurpassable and his technique the most dazzling since Paganini. At the end, he motioned me to join him on the platform and there was a standing ovation. The reviews were very enthusiastic… and the next performance at Fort Worth was equally well received. After Heiftez had finished his tour, he recorded the concerto. The record was made simply by recording each movement three times without stopping. When I asked him how it was possible for him to play so well without any practice, he replied, ‘I practiced it well to start with.’” That recording paved the way for the first European performance in Baden-Baden. In time, Rózsa conducted the work ten or fifteen times over the years, in both America and in Europe. As a critic writes, “the music of Miklós Rózsa tempers an arch romanticism with an innate classicism. Perhaps this reflects the fact that he was born in Hungary but trained at the Leipzig Conservatory. It is true both of his film music, where romanticism is rather more to the fore and his concert works, where form and substance never fail to satisfy.”

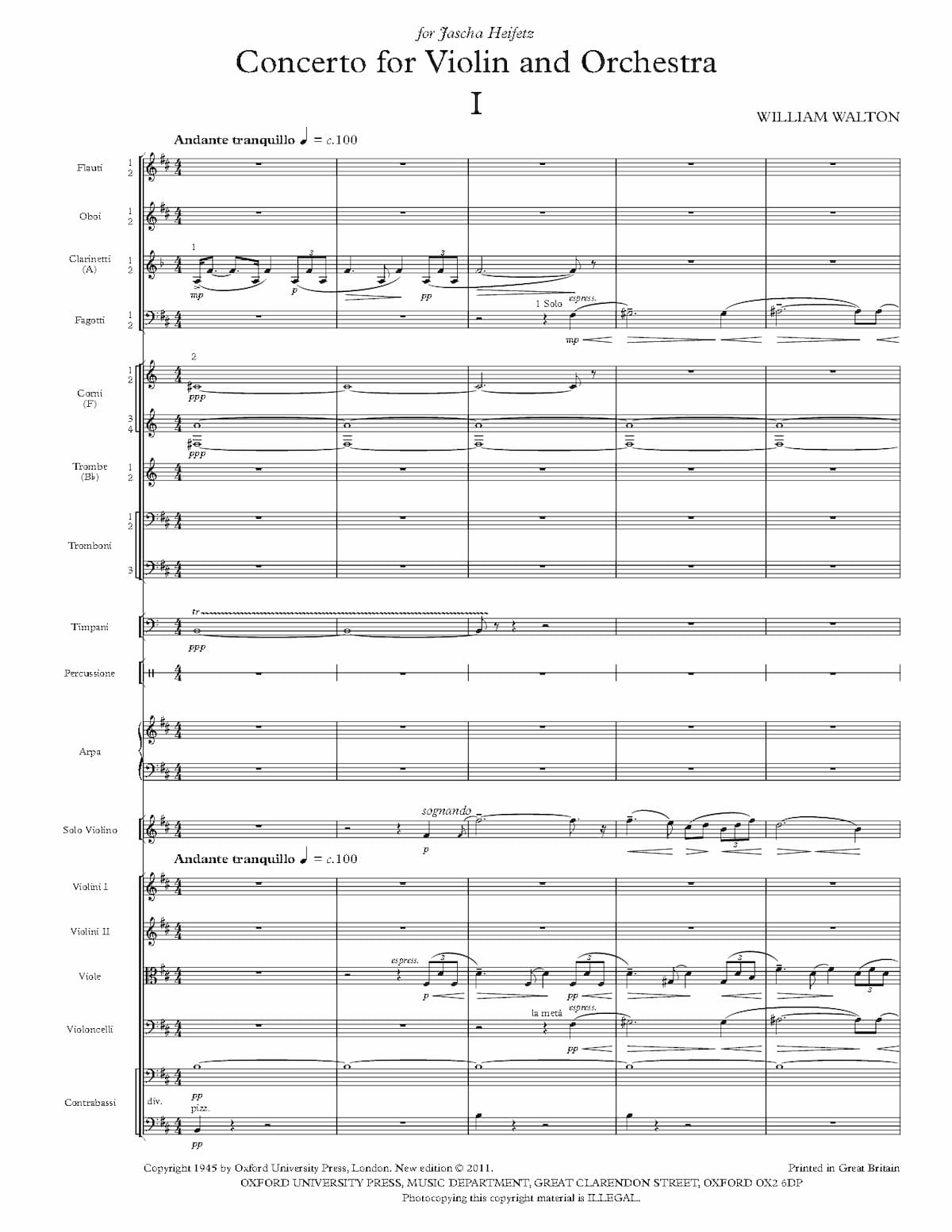

William Walton: Violin Concerto

In 1937, Jascha Heifetz sent a check for 300 pounds to William Walton to commission a violin concerto. Walton was delighted and quickly accepted the invitation. By sheer coincidence, at roughly the same time, the British Council also asked Walton for a violin concerto to sound at the World’s Fair in New York City in June 1939. Walton gladly combined both offers and insisted that Heifetz give the premiere performance. As his wife recalled, “William did not know how to make the violin part elaborate enough, and therefore worthy of Heifetz.”

William Walton

Even Walton started to have doubts, as he reported to a colleague, “Heifetz may not like the work; he may have other dates and be unable to play it. This I have not had time to find out, and at any rate, Heifetz is hardly likely to commit himself until he has seen at least part of the work. At the moment there doesn’t seem much to show him. Of course, I suppose in the case of Heifetz refusing, I can always find someone else, but it would be bad I think for the work.” Walton’s fear was justified, as Heifetz was not initially satisfied with the work at all. Heifetz wasn’t happy with either the first or second movement, and Walton “was having a great difficulty in making the last movement elaborate enough for Heifetz to play.” Walton was predictably stressed and even suggested that he would “never work on commission again.”

William Walton’s Violin Concerto

Walton was fearful that Heifetz would reject the work completely, but out of the blue, Heifetz cabled to “enthusiastically accept” the work. The world premiere was scheduled for June 1939, but Heifetz was not available. And since Heifetz had exclusive playing rights for two years, it all had to be postponed. In May 1939 Walton visited Heifetz in the US and they continued working through the piece. This process of revision continued until December 1939 when Walton finally gave Heifetz “permission to make any alteration in the score,” and Heifetz copiously did. In the event, the premiere performance was hailed as a “stirring performance of a work of character and quality, personal, intense, direct, straightforward. The use of the violin is felicitous, from soaring cantilena to brilliance.” However, Walton was still not satisfied and he revised the orchestration in 1943 and once again in 1950. When the Korean violinist Kyung-Wha Chung asked the composer why he had composed such a demanding piece, Walton answered, “It’s not my fault; it’s that damn Heifetz!”

Louis Gruenberg: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 47

Louis Gruenberg: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 47 (Jascha Heifetz, violin; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Pierre Monteux, cond.)

Louis Gruenberg © Wise Music Classical

The Russian-born American pianist and composer Louis Gruenberg (1884-1964) was an early champion of the music of Arnold Schoenberg and a highly respected film composer in Hollywood. Gruenberg wrote, “In an effort to appraise music today in Paris, London, Berlin, and Vienna, it becomes my firm conviction that the American composer can only achieve individual expression by developing his own resources, instead of submitting to the prevailing tendencies of various countries or blindly following the traditions of classical form.” These resources are vital and manifold, for we have at least three rich veins indigenous to America alone: Jazz, Negro spirituals, and Indian themes… America must be youthfully interpreted in a new idiom, a new technique invented to combine knowledge of tradition and the modern experiment… Music in Europe today is suffering from over-sophistication and perhaps America’s trouble is under-sophistication.” In the event, Gruenberg was overjoyed when Jascha Heifetz commissioned and premiered his Violin Concerto, Op. 47 with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1945.

Cyril Scott: Fantasie Orientale

Claude Debussy called Cyril Scott (1879-1970) “one of the rarest artists of the present generation.” It’s hardly surprising that the press started to call Scott the “English Debussy.” Scott dabbled in orientalism and he writes, “That I should appeal to Eastern taste is curious because I have never been to the East, nor have I heard much Eastern music. I can, therefore, only account for the fact by my extensive study of Oriental philosophy.”

Cyril Scott

Scott had studied with Humperdinck at the Frankfurt Conservatory, and together with fellow students Percy Grainger, Norman O’Neill, Roger Quilter and Balfour Gardiner, he was looking to “stand apart from the mainstream of conservative British composers.” Scott’s serious compositions, which include symphonies, operas, and extended chamber compositions, did not resonate with the public at all. Instead, he became primarily known as a composer of countless popular short songs and piano/violin pieces, including the Fantasie Orientale dedicated to Jascha Heifetz. Heifetz wielded tremendous influence over the musical establishment of his time and he decidedly inspired a number of violin masterpieces.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Don’t know if you can call of these works “masterpieces” ! Walton may be the only one even coming close to such a moniker…

I wouldn’t hesitate the least when it comes to Walton !!

His Viola Concerto is the greatest one of the past century and the violin concerto is also incredibly beautiful and exciting !!