In Germany, in the early years of the 20th century, with rapid industrialization and growing urban populations, we see a return to, and a longing for, the simpler past of rural life, in opposition to the fast-paced life of the cities. As discussed in my previous article, in the last years of 19th century there was also a renewed interest in Arcadian themes not only in France, but in Germany as well. This nostalgic yearning found expression in the works of Arnold Böcklin, Max Klinger and Hans von Marées, who would later inspire the younger generation of German Expressionist painters, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Franz Marc, August Macke and Erich Heckel.

In Germany, in the early years of the 20th century, with rapid industrialization and growing urban populations, we see a return to, and a longing for, the simpler past of rural life, in opposition to the fast-paced life of the cities. As discussed in my previous article, in the last years of 19th century there was also a renewed interest in Arcadian themes not only in France, but in Germany as well. This nostalgic yearning found expression in the works of Arnold Böcklin, Max Klinger and Hans von Marées, who would later inspire the younger generation of German Expressionist painters, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Franz Marc, August Macke and Erich Heckel.

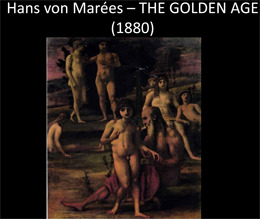

Returning to the mythical Greek themes of men and women in idyllic landscapes, involved in dancing and music making, Marées’ paintings emit a timeless, almost abstract beauty, where time as well as subject matter and content seem suspended. The paintings carry titles such as ‘Men by the Sea’ and ‘The Golden Age’, unspecified as to their precise settings, but evoking this lost ‘Golden Age’ of youth and innocence.

The writer Thomas Mann, owner of Marées’ painting ‘The Spring’, used it as inspiration for his novel ‘The Magic Mountain’, which expresses the literary concept of Arcadia:

“And all the sunny regions, these open coastal heights and laughing rocky basins, even the sea itself out to the islands, where boats plied to and fro, was peopled far and wide. On every hand, human beings, children of sun and sea, were stirring or sitting. Beautiful young human creatures, so blithe, so good and gay, so pleasing to see”…. (Catalogue of the Arcadian Exhibition, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2012, p.196).

Many German painters, including those mentioned above, joined the ‘return to nature’ movement, fleeing academic urban circles in order to settle in remote rural artists’ colonies, such as on the shores of the Baltic and North Sea and in small villages outside major cities, in ‘unspoiled’ natural surroundings. In addition to Marées’ influence, they were also inspired by the French painter Paul Gauguin, who, escaping Paris, had established himself in Tahiti in the 1890’s to seek the simple, unspoiled life in ‘paradise’. It is important to remember that Gauguin himself had been influenced by the 18th century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s critique of the decadence of Western society, particularly its cities. According to Rousseau, society and city life corrupts, but man could find himself again in unspoiled nature — in Rousseau’s case, the Alps. This ‘return to nature’ theme was of course also a central theme in Romanticism in literature, the arts and music.

Many German painters, including those mentioned above, joined the ‘return to nature’ movement, fleeing academic urban circles in order to settle in remote rural artists’ colonies, such as on the shores of the Baltic and North Sea and in small villages outside major cities, in ‘unspoiled’ natural surroundings. In addition to Marées’ influence, they were also inspired by the French painter Paul Gauguin, who, escaping Paris, had established himself in Tahiti in the 1890’s to seek the simple, unspoiled life in ‘paradise’. It is important to remember that Gauguin himself had been influenced by the 18th century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s critique of the decadence of Western society, particularly its cities. According to Rousseau, society and city life corrupts, but man could find himself again in unspoiled nature — in Rousseau’s case, the Alps. This ‘return to nature’ theme was of course also a central theme in Romanticism in literature, the arts and music.

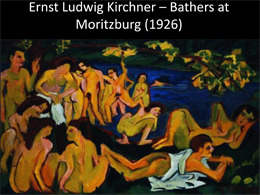

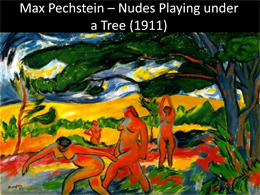

In Germany, this concept carried over into the “Freikörperkultur” (‘nudism in nature’), which advocated the freedom of men and women in nature, vegetarianism, and sun and air therapy. In 1905, in the city of Dresden, four architecture students, Kirchner, Bleyl, Heckel, and Schmitt-Rottluff, founded the artist’s association, ‘Die Brűcke’ — later joined by artists such as Otto Műller, Emil Nolde, and Max Pechstein. Their aim, again, was to escape the modern city, to enjoy the rural, simpler life, in which art would be reconciled with nature and humanity. In addition, they tried to establish a close relationship between artists’ community and the public — hence the name ‘Die Brűcke’ (The Bridge).

These artists’ painted subjects, usually in the nude, are shown frolicking in nature, where they blend into the setting rather than being the primary focus of the painting. Their painting style, usually using broad brush strokes for foreground, background and figures, eliminated facial features, thus de-personalizing the depicted models and embedding them in the surrounding landscape. The vivid color scheme of their paintings, reminiscent of the ‘Fauves’ painters in Paris (Braque, Derain and early Matisse), also emphasized the harmony of figure and landscape — in that they were both presented in the same fashion. The painter Pechstein formulated the relationship as follows: “I had the good fortune to always have had with me, in total naturalness, a human being whose movements I could absorb. Thus, I continued to understand man and woman and nature as one” (ibid, p. 200).

These artists’ painted subjects, usually in the nude, are shown frolicking in nature, where they blend into the setting rather than being the primary focus of the painting. Their painting style, usually using broad brush strokes for foreground, background and figures, eliminated facial features, thus de-personalizing the depicted models and embedding them in the surrounding landscape. The vivid color scheme of their paintings, reminiscent of the ‘Fauves’ painters in Paris (Braque, Derain and early Matisse), also emphasized the harmony of figure and landscape — in that they were both presented in the same fashion. The painter Pechstein formulated the relationship as follows: “I had the good fortune to always have had with me, in total naturalness, a human being whose movements I could absorb. Thus, I continued to understand man and woman and nature as one” (ibid, p. 200).

Arcadian themes in 20th century music, as we have seen in my last article, found their expression in Debussy’s Daphnis and Chloe, his Pelléas and Mélisande and in the artistic creations of the Ballets Russes, such as ‘The Rite of Spring’, ‘Les Noces’ and ‘The Afternoon of a Faun’. However, in Austria a new trend started to emerge with the ‘Second’ Viennese music generation of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern (the ‘First’, of course, being Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven).

Schoenberg

Das Buch der hangenden Garten, Op. 15

Schoenberg’s composition, ‘The Book of the Hanging Gardens’, a fifteen-part song cycle composed between 1908 and 1909 and based on poems by Stefan George, is not about a ‘love affair’ of Arcadian shepherds in a beautiful setting, but rather the love affair of two adolescent youths — an ill-fated affair — with the young woman leaving the garden, which then falls into ruin. The metaphor of the disintegration of the garden is replicated in the music itself. Schoenberg leaves traditional harmony, tonality, and classical structure behind and moves into the new world of atonality, which Berg and Webern continued to explore. Just as in the paintings of the Dresden ‘Brűcke’ group, the emphasis of artistic creation is now focused on the structure of the art work itself — be it painting or music.

More Arts

-

In Memory of the Past: Goethe’s ‘Erster Verlust’ A century of art song interpretations of first love and loss

In Memory of the Past: Goethe’s ‘Erster Verlust’ A century of art song interpretations of first love and loss -

Musicians and Artists: Holt and Goya Discover inspirations behind Simon Holt's piano work Tauromaquia

Musicians and Artists: Holt and Goya Discover inspirations behind Simon Holt's piano work Tauromaquia -

Musicians and Artists: Adams and Rothko Transforming Mark Rothko's color field painting into music

Musicians and Artists: Adams and Rothko Transforming Mark Rothko's color field painting into music -

Musicians and Artists: Gould and Burchfield Morton Gould's musical tribute to artist Charles Burchfield

Musicians and Artists: Gould and Burchfield Morton Gould's musical tribute to artist Charles Burchfield