Ensembles and Bands That Preserve and Evolve Ancestral Musical Expressions

Song Dynasty (12th century) painting featuring two dizi players

It is a horrifying fact, but as many as half of the world’s 7,000 languages are expected to be extinct by the end of this century. “The effect of language loss is culturally devastating, as each language is a key that can unlock local knowledge about medicinal secrets, ecological wisdom, weather and climate patterns, spiritual attitudes and artistic and mythological histories.” And when culture dies, music dies. Thankfully a good many dedicated musicians have decided to preserve and evolve ancestral musical expressions. One such dedicated professional is Tang Jun Qiao, an esteemed professor at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, and the most influential “Dizi” virtuoso in China. We still don’t know the precise origins of the Bamboo Flute, but the instrument was probably introduced into China from Central Asia during the Han dynasty. Transverse flutes have clearly been around for a very long time, and various types developed over the centuries.

DiZi: Chinese Traditional Bamboo Flute

Tang Jun Qiao

Much of the solo repertory composed during the 20th century has been written for an instrument called “bangdi,” also known as “gaodi” (high flute) or “duandi” (short flute).

The instrument is constructed from various species of bamboo, and the tube is closed at the blowing end with a cork. Distributed along the upper surface are a blowhole, membrane hole and six finger holes. Covering the membrane hole is a vibrating membrane, producing the characteristically buzzing sound. Two end-holes on the underside define the length of the vibrating air column and are frequently used to attach a string or tassel. Traditional flutes produce a temperament of mixed whole-tone and three-quarter-tone intervals, and its pure and mellow tone makes the dizi most suitable for expressing delicate and understated moods.

Tang Junquiao: “Dizi Concerto “Flying Song”

Different sizes of Dizi

As a celebrated educator and inspired teacher, Tang Jun Qiao has been at the forefront of passing her vast knowledge of Chinese traditional folk music to the next generation. Initially, she learned to play the instrument from her father, and in due course she became the only Chinese player of folk music regularly invited to cooperate with world famous orchestras. The Washington Post praised Tang for “her virtuosity in a nearly unlimited breadth of timbres and superb control of breath.” She was also invited to record the bamboo flute and bawu parts in Tan Dun’s composition for the film “Crouching Tiger-Hidden Dragon,” and her incredible skills as a performer has also inspired a substantial number of contemporary Chinese composers to write dedicated concertos for the bamboo flute.

Beijing Bamboo Orchestra

A large number of students studying bamboo flute at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music under Tang’s supervision, have won national awards for performances of traditional instrumental music. With support from the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, she founded the “Tang Jun Qiao Bamboo Flute Orchestra” in 2013. Tang serves as the president and musical director of this group of highly talented students known as the “Dream Team of Bamboo Flutists.” Affiliated with the Bamboo Research Center Institute for advanced studies at the Shanghai Conservatory, the orchestra has been invited to participate in cultural exchanges, arts exhibitions, and numerous concerts. Her efforts have spawned “The Beijing Bamboo Orchestra,” also known as China’s only “green orchestra.” This unique ensemble features roughly 30 instruments, all fashioned from bamboo.

Beijing Bamboo Orchestra

Trinity College harp, Dublin, Ireland, July 2017

Traditional music has always been an important part of Irish culture. In fact, as a scholar writes, “there seems to be a particular affinity to music in the Irish national character.” Traditional music is a central element of Irish identity, and it’s no accident that the state symbol of the Republic of Ireland is the harp. Reflecting the predominant social and cultural strains in modern Ireland, its traditional music is largely Celtic (Gaelic or Irish) and British (English and Scottish) in origin. Its main contemporary forms are songs in Irish and English and instrumental airs and dance tunes. As you might well imagine, traditional music has had a very long history, and it has enjoyed a very popular revival in the second half of the 20th century, especially among younger people. It is also performed and listened to in various centers of Irish settlement abroad, chiefly in Britain, Australia, and the USA.

Ireland One Penny Coin with Harp

A critic writes, “the reasons for the strength of Irish traditional music are partly historical and social: political conditions have fostered the oral arts of song, instrumental music, dance and storytelling rather than the visual and plastic arts; traditional rural society, non-industrial and conservative, survived longer in Ireland than in western Europe generally; and the relative smallness of the country and its population enables easy access to all varieties of live performance.” The revival and renewal of older traditions has continued strongly until the present day, and traditional instrumental music is to an extent now part of youth culture. Take for example the folk band “The Gloaming,” who combine the rich Irish folk tradition with the New York contemporary music scene and produce traditional Irish music with a modern twist.

The Gloaming: “The Sailor’s Bonnet”

The Gloaming

“The Gloaming” formed in 2011, and consists of fiddle player Martin Hayes, guitarist Dennis Cahill, sean-nós singer Iarla Ó Lionáird, hardanger fiddle player Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh, and pianist Thomas Bartlett. As fiddle player Martin Hayes explains, “the band play a traditional music form that speaks to the now, that speaks to the moment and then also has a cultural resonance. Part of the music is quite elemental and very old and traditional, but there is a fascination among the musicians to explore all kinds of modern music for new ideas. The feeling is that we love the depth of the tradition, but we’re not interested in it as an artifact. It has to be a form of expression in this current moment.” At the heart of the band is the fiddle, surely one of the most popular instruments in traditional Irish music. There seems to be a huge variety of stylistic approaches to fiddle playing in various regions of Ireland, and even within each region. Hayes explained, “It’s an instrument that doesn’t get taught in the normal, formal way that you have in music academies and conservatories of music where they have classical music. Instead, with Irish music, there are a lot of the musician coming to know the instrument in their own unique way and coming to find solutions for playing tunes unique to them. So you end up with a lot of very distinctive style and a lot of variety.” In the end, “The Gloaming” produces a sound that is a bit more modern and connected to the sounds of the world around us right now.

The Gloaming: “Boy in the Gap/The Lobster)

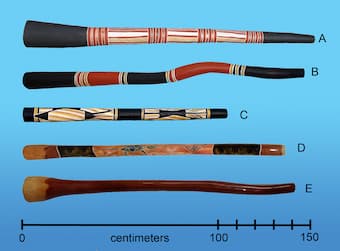

Australian didgeridoos

If we are talking about indigenous instruments, it really doesn’t get any more indigenous than the didgeridoo. This wooden drone pipe, played with varying techniques in a number of Australian Aboriginal culture is “often regarded as a pan-Aboriginal instrument.” Mythology tells us that the didgeridoo is a “Dreamtime creation,” while the historical origin of the instrument is uncertain. The instrument is called by different names in various cultures, and it has been suggested that the English name “didgeridoo” may have been an onomatopoeic designation describing the sounds produced by the instrument. The instrument is fashioned from termite-hollowed trunks or branches of any of a number of trees, and a feature of traditional performance is “a technique of circular breathing, in which the player reserves small amounts of air in the cheeks or mouth while blowing. This allows the player to snatch frequent small breaths through the nose while simultaneously continuing the drone pitch by expelling the reserved air.”

In traditional contexts, the didgeridoo is especially associated with public ceremonial genres and nearly always used as an accompanying instrument. “It is played by a single male accompanying one or more male singers who also play pairs of hard wood clapsticks. In a number of genres the performance may also include dancing by women and/or men.” Over the past couple of generations contemporary bands have used the didgeridoo, including “Yothu Yindi,” an Aboriginal band from the territory’s northeastern coast. “They are recognized as a pioneer of Australian-based world music that mix indigenous music and international popular styles to raise awareness of traditions and issues affecting indigenous peoples.”

Yothu Yindi: “Treaty”

Didgeridoo and clap sticks

For many listeners, the idiomatic sound of the didgeridoo has become an easily recognizable icon of Aboriginal Australia. “On a global level the didgeridoo has found significant use in culturally hybrid world music groups, in new age performance (both in aesthetic-orientated and healing-orientated contexts) and in neo-tribal didgeridoo circles that have sprung up in many urban areas.” A good many of these new age interpretations have little to do with conceptions of the instrument in traditional Aboriginal societies, and it has incited a good deal of early 21st-century cultural controversy. “While some non- indigenous people have been given permission from many traditional owners to play the instrument, other Aboriginal communities feel allowing non-indigenous people to play the instrument is cultural theft.”

Australia Aboriginal Culture

Recently, an Aboriginal academic has accused a publisher of gross cultural insensitivity over a new book that included didgeridoo lessons for girls. The general manager of the Victorian Aboriginal Education Association protested, saying “I would say from an Indigenous perspective, this is an extreme mistake, but part of a general ignorance that mainstream Australia has about Aboriginal culture. We know very clearly that there is a range of consequences for females touching a didgeridoo, it’s men’s business, and in the girl’s book, instructions on how to use it, for use it is an extreme cultural indiscretion. The consequences for a girl touching a didgeridoo can be quite extreme, and can lead to infertility… I won’t even let my daughter touch one…. as cultural respect. And we know it’s men’s business.” With all due respect, I personally couldn’t disagree more. The function of all instruments and the gender of its users is not a universal constant but subject to changes over time. It seems to me that sharing ancestral knowledge with people, irrespective of background, creed or gender, will ultimately contribute to the survival of this unique heritage.

Dr. Didg: “Made Ya Mine”

Andean instruments

For our next stop on this “Walkin’ round the World” tour we visit the Andean landscape in South America. In Pre-Colombian times, music was a sacred art, a powerful source of communication with the divine world, associated with religious or agricultural rituals and wars, usually accompanied by singing that was high-pitched and nasal. “The Incas only used the word ‘taqui’ to describe dance, music and singing. They did not differentiate among the three, because for them they were strictly interconnected.” The Incas are thought to have had just two types of musical instruments, winds and percussion. Nevertheless, they spread their style of music as far north as Colombia and as far south as Chile. As such, the haunting sounds of bamboo pipes have been part of the Andean landscape for over two thousand years. Subsequently, Europeans brought their music, musical influences and instruments. Local wind and percussion instrument mixed with exotic stringed and percussive instruments from Europe to create a new and unique kind of Andean Folk music.

INCA: “The Peruvian Ensemble”

Los Kjarkas

Over time a classic Andean sound developed that relied on the sounds of the kena (wood or bamboo flute) and siku (bamboo pipes), accompanied by a charango (10-stringed guitar made of an armadillo shell) and the bombo (large wooden drum). This kind of standard ensemble developed in the 1960s alongside the economic migration of rural indigenous people to large urban centers. During the 1960s, the Hermosa brothers and Edgar Villarroel founded “Los Kjarkas,” a Bolivian band from the Capinota province in the department of Cochabamba. The name of the band derives from the Quechua word “Kharka,” which basically means strength.

Over time “Los Kjarkas” became one of the most popular Andean folk music bands, performing a variety of styles including the Saya, Tuntuna, Huayno, and Carnavales. The band quickly became famous in Bolivia, but also started touring throughout South America, the USA, Europe and Japan. However, they stayed closely connected to their community and one member even became the mayor of the city of Cochabamba. In addition, the music ensemble has founded two schools teaching Andean folk music. One is located in Lima, Peru, and the other one in Ecuador. “Los Kjarkas” is unquestionably the most famous folkloric music group in South America with over 350 original compositions in their repertoire. In fact, their music has become the symbol of Bolivian culture and passion in Latin America.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Los Kjarkas: Concert Performance 2003