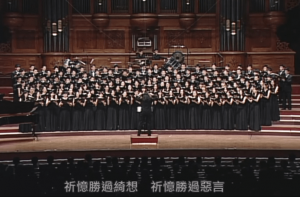

Sperry’s arrangement of A.R. Rahman’s Zikr, sung by the

National Taiwan University Choir

That outlook helps Ethan Sperry take on the daunting challenge of transplanting music between disparate traditions. Sperry has arranged Carnatic music compositions into the standard form of Western choral music: pieces to be sung by a four-part harmony choir comprising of soprano, alto, tenor, and bass.

“I’m seeing, well hearing actually, American choirs making a much wider variety of sounds,” Sperry said. “I’m not referring to pieces that require expanded vocal techniques, I’m talking about choirs changing their sound to suit the piece they are performing. I think this is at the crux of great choral music-making, and I find it very inspiring. Britain has this amazing choral tradition where they all sing so cleanly and so perfectly and I think we have been trying to emulate that for a long time. In doing so we created some beautiful choirs, but I think we missed a lot of musicianship along the way. American choirs have been much more adventurous in programming, not only in championing modern music but in exploring the music of other cultures.”

In Sperry’s own exploration of Carnatic music and its adaptation to Western choirs, there necessarily had to be compromises. Although most Carnatic music is written to be sung, the structure is very different. The basic unit of a Carnatic composition, known as a kriti, has three distinct components: pallavi (meaning “sprouting,” the equivalent of the refrain of Western music) anupallavi (meaning “continuation of the sprouting,” the succeeding verse, optional) and charanam (meaning “feet,” the last and longest verse which wraps up the song, the final line of which bears the composer’s musical signature). And a Carnatic music concert (katcheri) usually has several sections: a tana varnam (somewhat like a warm-up or an etude), simple and complex kritis (usually 7-9 per concert) and a lyrical closing piece like a padam, mangalam or thillana. Moreover, a hallmark of such concerts is improvisation, the singer and the accompanist having great leeway within their musical parameters. So no two concerts are alike even when the same piece is performed, a far cry from choirs that sing using sheet music, deviations from which crook eyebrows or evoke outright censure.

So how does one take Carnatic music and arrange it for a choir?

Sperry’s approach in negotiating these obstacles is better understood by viewing the performance of a Carnatic composition and then viewing Sperry’s arrangement of the same piece for a four-part harmony choir.

The basic katcheri ensemble consists of the singer, accompanied by a drummer using a drum like the mridangam or tavil or even an earthen pot (ghatam), and supported by a background drone note (shruti) generated by a stringed instrument called the tambura or by the shruti box, a bellows-operated instrument similar to the harmonium. The drone serves as a pitch reference and is the closest the performance gets to using harmony. There may be additional instruments like a violin and a kanjira (a small tambourine).

Here is a video of a thillana (a rhythmic piece that usually is the last item in a concert) composed and sung by a leading Carnatic musician, M. Balamuralikrishna.

Two videos of Ethan Sperry’s arrangement of Balamuralikrishna’s Thillana in Dwijavanthi follow. These are performed by two of America’s finest high school choirs: the Martin High School Chamber Singers, Arlington, Texas, and the Winton Wood High School (WWHS) Varsity Ensemble, Forest Park, Ohio (who, among other distinctions, have recorded two CDs with the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra and performed in the 2008 Pre-Olympic Festival in China). Because of the differing visual and audio quality of the recordings and the cinematography (for instance, close-up shots showing how the singers vocalize the notes), both video clips have something to offer to the viewer.

Sperry has the sopranos and tenors begin with harmonic overtone singing to simulate the droning of the tambura / shruti box. The tenors start with an octave drone of C and C, with the sopranos joining in the second measure creating antiphonal sound as they drone at a fifth interval, C and G, with the C for the sopranos at the same pitch as the top C for the tenors. The basses layer a harmony atop the droning as they burst into song in the third measure, “Dhi-ra-naa Naa, Dhi-ra-naa.”

Next, Sperry introduces the “call and response” pattern, a characteristic feature of Indian music. Even in a katcheri where there is only one singer, when the singer calls, a musician responds. There are also passages where the singer is silent and one or more musicians hold court, dazzling the audience with their mastery over their chosen instrument. Sperry brings the “call and response” into play when the altos respond to the basses’ call with their own response, “Dhi-ra-naa Naa, Dhi-ra-naa, Thaa-no, Tha-na”, and by now we are well into the composition.

The Carnatic katcheri only uses a few instruments, but rather than attempt to use these Indian instruments for a choir or find similar Western instruments, Sperry opted for an a capella arrangement sprinkled with vocables like “dng” and “k” to imitate the sounds of the mridangam or the kanjira, in addition to the harmonic overtone singing. All the “instruments” that we hear, all the droning, jingling, and drumming, are made by the human voice. There are constant rhythmic changes and swapping of parts.

The next consideration is: what is being sung? Earthsongs, the publisher of the sheet music of this Sperry arrangement, states: “Other syllables used in this piece such as ‘Ta-na-na’ and ‘Ta-ki-ta’ are not purely nonsense syllables like ‘doo-doo-doo.’ These syllables are taken from a rhythmic solfège language used by musicians in India called sollokattu [sic].”

Solfège (from the Italian solfeggio) is a form of solmization: that is, attributing a distinct syllable to each note in a musical scale. The solfège language used in South India, solkattu (in Tamil, “bundles of syllables”) is a system of reciting rhythmic syllables while simultaneously counting the tala (meter) by hand, such as by the clapping of hands. The spoken component of solkattu is referred to as konnakol (which can be loosely but aptly translated as “rhythm is king” or “rhythm rules”). Konnakol is the vocal imitation of percussion sounds and patterns. Compositions in konnakol can be spoken as well as sung, as demonstrated by the video below of boys of varying ages reciting a konnakol composition written by percussionist Vikku Vinayakram. The introduction is by the British musician John McLaughlin who has repeatedly acknowledged konnakol as having played a foundational role in his personal musical journey.

Sperry’s arrangement omitted parts of the concluding section of Balamuralikrishna’s composition. In its place, Sperry tacked on several konnakol phrases (for instance, Ta-ka-di-mi and Ta-ka-ju-na) that are not part of the original. Also, Balamuralikrishna’s composition as a whole was sung at a fairly even, almost leisurely pace. But as the boys on the beach demonstrated, konnakol can be belted out as well as chanted slowly. When Sperry added his own konnakol phrases toward the end of his arrangement, he also upped the tempo. What begins as a slow rubato (in Italian, “stolen time”) of 85, moves to a faster 100, and then rockets to a crescendo in the region of 180+ (that is, as fast as the conductor wants it or the choir can sing it) before decelerating at the very end.

All along, several things go on simultaneously: call and response, swapping parts to and fro, and continuous rhythmic changes. There is also a section where the tenors and sopranos sing while the altos and basses (like the boys on the beach) don’t sing but speak Ta-ka-di-mi, Ta-ka-ju-na in a flat voice, imitating the shruti-box/tambura drone through the sound of the spoken word rather than through humming.

Sperry, then, has brought considerable inventiveness in this choral arrangement.

Ecclesiastical Music

Thiru Pallandu is a sacred chant composed by Periya Alwar (one of the last among the lineage of the Alwar saints of Tamil Nadu) who lived around 900 AD in Sri Villiputtur, Tamil Nadu. Composed in Tamil, this chant is part of the larger Naalaayira Divya Prabhandham, a musical compilation of 4000 stanzas. A paean to Lord Vishnu, Thiru Pallandu is recited in the Vishnu temples all over southern India.

Sacred music is also part of the Western choral tradition. And such choral singing started as plainsong, sung in unison, as Thiru Pallandu is in India today. Around 1400 CE, choirs began singing sacred music in polyphonic harmony. Sperry only uses the first pasuram (stanza) of Thiru Pallandu but prolongs his arrangement longer by multiple repetitions of the same lyrics. Interestingly, this piece by Sperry is often performed by either all-male or all-female choirs. Here is a performance by Prime Voci, the Seattle Girls Choir:

Sperry again begins with the singers vocalizing a drone, and throughout the piece mimicking musical instruments as he did in his Dwijavanthi arrangement. Sperry also includes Konnakol solfège phrases like Ta-ki-ta and Dhi-na-ka into his arrangement for rhythm and effect – a feature capable of raising eyebrows (if not hackles) in India among orthodox Hindus who regard the sacred composition to be recited or sung in a plain way from the heart (like the plainchant of medieval Europe), and not as something resembling entertainment.

However, in the evolving choral tradition, musical and verbal embellishments are deemed as adding to the splendour of the piece much as a colourful stained glass window lights up an otherwise drab church. Guillaume de Machaut’s Kyrie (from La Messe de Nostre Dame) and Samuel Barber’s Agnus Dei are good examples.

It is not just Hindu sacred music that interests Sperry. He has also adapted A. R. Rahman’s music arrangement for the Urdu devotional Zikr as a cantus (the mediaeval form of choral singing, usually in polyphonic style, and in the highest range of voice). Zikr (or Dhikr) refers to a technique from the Sufi tradition of Islam which goes back at least 700 years, and emphasizes that short phrases or prayers (taken from the Quran or the Hadith) repeatedly recited either aloud or mentally ushers one closer to the divine. The word “Hu” in Sufism is gender-free; God is not labelled as “he” or “she.” Some lines:

“Zikr aman hai, zikr hai fatah, zikr shifa hai, zikr hai dawa.”

(Zikr is peace; zikr is victory; zikr is healing; zikr is the cure)

“Haq laillaha illallah.”

(There is no other truth save God.)

“Hu Allah Hu Allah Hu.”

(Just God – or – There is no reality other than God)

Sperry is a friend of A.R. Rahman, who was born a Hindu with the birth name Dileep Kumar but later converted to Islam, taking the new name Allah Rakha (A.R.) Rahman. Sperry has commented that despite having composed music for thousands of songs, “…Zikr is his only statement of [his] faith in music.” That said, this Sufi practice of repetition is remarkably similar to the concept of japa yoga in Hinduism (or, for that matter, using the rosary in prayer in Catholicism).

“I am most proud of Zikr,” Sperry says, adding, “The media gives a lot of airtime to a relatively small group of Muslims who are terrorists, and almost no attention to the millions of Muslims (138 million in India alone) who are not. I hope this song will help some people understand that there’s much more to Islam than Al Qaeda.”

(To be continued)

By Vishwas Gaitonde

This Article first appeared on Serenade Magazine on June 3rd, 2018.