Johannes Brahms

In 1881, Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) wrote to his friend Elisabeth von Herzogenberg that he had finished “a tiny little piano concerto with a wisp of a scherzo.” At that time, Elisabeth could scarcely have known that Brahms had just completed a monumental work in four movements that would radically change our conception of what a concerto should be. As might be gauged by the unusual number of movements for a concerto, Brahms was working on an ingenious hybrid between the symphonic and concerto genres.

For one, the successful development and musical realisation of the thematic materials that Brahms sketched after his first trip to Italy clearly required an orchestral setting. In addition, the primacy of virtuosity usually assigned to the piano soloist was called into question by the principle of interpretation, thereby establishing an apparently equal relationship between the soloist and the ensemble.

This fact was clearly recognised in an extensive review by Franz Liszt, who wrote “the work possesses the pregnant character of a distinguished work of art, in which thought and feeling move in noble harmony.” But what had prompted Brahms to consider this intimate symbiosis between piano and orchestra in the first place? To arrive at a possible answer, we might first have to look at his Symphony No. 2, a work Brahms completed in record time in the summer of 1877. After spending nearly fifteen years on the completion of his First Symphony, Brahms essentially completed the Second during his summer holiday in Carinthia. Having finally overcome his “Angst” and escaped “Beethoven’s shadow,” Brahms composed a spontaneous — one is almost tempted to say jovial work—that combined the “light and dark, the lyrical and forceful, the extroverted and introspective, while organically growing all four movements of the composition from the very first three notes.” With this symphonic conception of unity in mind, Brahms began to draft the thematic material for a three-movement piano concerto in 1878. Brahms habitually puts aside unfinished compositions, but in this case the completion of the work was interrupted by his collaboration with Joseph Joachim on the D major Violin Concerto.

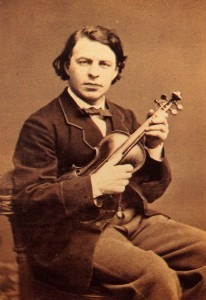

Joseph Joachim

We don’t know exactly when Brahms actually started to draft the Violin Concerto, but he was almost certainly drawing his musical and conceptual inspiration for both concertos in the same well. Interestingly, it was actually the Violin concerto that was, from the very beginning, planned in four movements. One of the middle movements, in a clear deference to the symphonic tradition, was intended to be a lively “Scherzo.” However, before Joachim even managed to see the score, Brahms had decided that the two middle movements did not adhere to his high standards, or alternately, did not fit with his overall conception of the work. “I have written a feeble little adagio instead,” he reports to Joachim. However, Brahms did not entirely reject the discarded “Scherzo.” Rather, he thoroughly reworked, reshaped and orchestrated the movement, and it eventually reappeared as the second movement of the B-flat Piano Concerto, which was finished on 7 June 1881. The Brahms Second Piano Concerto — and of course the Violin Concerto as well — are the direct musical consequence of the composer’s work on the Second Symphony.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 (Krystian Zimerman, Leonard Bernstein, Wiener Philharmoniker)