Seven students of Paul Gilson created their music collective Les Synthétistes (The Synthetists) on the occasion of their teacher’s 60th birthday in September 1925. They wanted to create a distinctive modern Brussels sound that was different from the late-Romantic sound that was still so prevalent in Europe but developed a modern aesthetic with balanced and defined forms.

One of their initial problems was that there were no professional symphonic orchestras in Brussels, outside the opera orchestra. The first group that they worked with was Royal Band of the Belgian Guides and a repertoire of 75 works for wind band were created. Few of the works were never published and then WWII eclipsed their achievements.

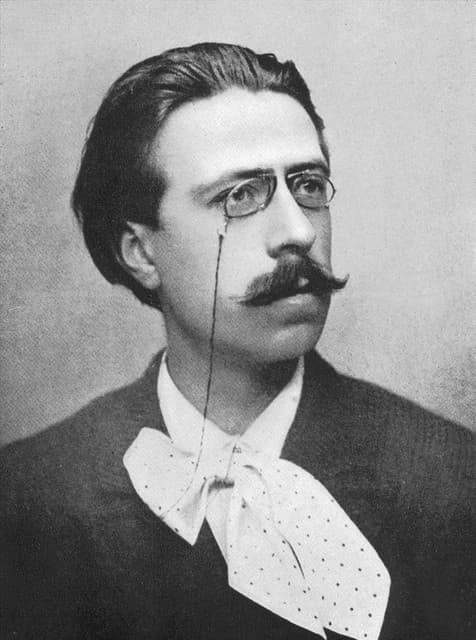

Paul Gilson

The seven were René Bernier, Francis de Bourguignon, Gaston Brenta, Théo Dejoncker, Marcel Poot, Maurice Schoemaker, and Jules Strens.

Les Synthétistes, 1930 (From left to right: Francis de Bourguignon, Marcel Poot, Maurice Schoemaker, René Bernier, Gaston Brenta, Jules Strens, and Théo Dejoncker)

Jules Strens (1893–1971) was at the Brussels Conservatory studying violin when he decided to expand into composition. Taking advice on orchestration from Gilson, he improved on his self-taught skills and in his Gil Blas, Op. 2, of 1921, wrote a work that won the Concerts Ysaÿe composition competition in 1922. The oboe stands for our eponymous hero as we follow him from his low-born life to his final career in the royal court and a wealthy retirement.

Jules Strens: Gil Blas, op. 2 – Theme: Allegro vivo (Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force; Matty Cilissen, cond.)

Marcel Poot (1901–1988) started at the Brussels Conservatoire as a pianist but Gilson talked him into composition and he ended up writing over 30 works for wind band. His 4-part suite Tartarin de Tarascon tells the story of the travels of Tartarin from his native town of Tarascon in southern France to the wilds of Algeria where he not only falls in love but has to deal with a lion. The exotic setting gives Poot the opportunity to write an Oriental dance (we’ll ignore the fact that Algeria is in Africa, not Asia!).

Marcel Poot: Tartarin de Tarascon, Humorous Suite – III. Danse orientale (Oriental Dance) (Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force; Matty Cilissen, cond.)

Francis de Bourguignon (1890–1961) started out as a piano virtuoso until he was wounded in WWI and spent his recovery in England. His next port of call was Australia, where he was permanent accompanist to the soprano Nellie Melba, accompanying her on her world tours from 1915 to 1920. He spent the next five years as a concerto pianist until he returned to Brussels in 1925. He took lessons from Gilson, whom he knew from his time at the Conservatoire, and developed his own style, which took its cues from the many varieties of modern music he’d heard during his decade of touring. Récitatif et Ronde seems to summon up the sounds of both Hindemith and Stravinsky.

Francis de Bourguignon: Récitatif et Ronde, Op. 94 (Michaël Tambour, trumpet; Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force; Matty Cilissen, cond.)

Gaston Brenta (1902–1969) didn’t attend the Brussels Conservatoire but, instead, was a private student of Gilson’s. His style revolved around a traditional tonality, coloured with rich chromaticism, but laid in a strong, clear structure supported with brilliant orchestration. In this choreographic fantasy, there’s more than a little of the orientalism of the Russian National School. In the middle of the great palace of Zo’har, a monster rises, and all is chaos, until Naim, the king of Zo’har (English horn solo), his sister, and her husband (cornet and trumpet solos) take on the monster, only to be defeated in the end by an immense rain of sulfur as the city is crushed.

Gaston Brenta: Zo’har, Choreographic Fantasy (Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force; Matty Cilissen, cond.)

Théo De Joncker (1894–1964) started studying with Gilson in 1907 and started his career as a conductor. As a composer, it wasn’t until he joined Les Synthétistes that his vague and mysterious style found a home in writing music to accompany actions in silent film. Guitenstreken was written to describe pranks – both on the screen and in the orchestra as fragments of diatonic and chromatic scales fly around the ensemble.

Théo De Joncker: Guitenstreken (Gaminerie) (Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force; Matty Cilissen, cond.)

Maurice Schoemaker (1890–1964) was another who took private lessons with Gilson. He was the only one to keep to a late-Romantic style, perhaps because he was the oldest of the Brussels Seven.

Maurice Schoemaker: Brueghel Suite, Symphonic Variations (1928 version for wind band) – III. March (Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force; Matty Cilissen, cond.)

René Bernier (1905–1984) was the youngest of the group and was the one most unlike Gilson in his writing. He was also described as ‘the most French composer’ of his contemporaries, with comparisons being made to Debussy. Epitaphe is a brief lament, with a funeral march in the muted brass and drums.

René Bernier: Epitaphe (1923 version for wind band) (Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force; Matty Cilissen, cond.)

Finally, we hear music by the master himself. Paul Gilson (1865–1942) himself had no formal training but many years of composition for various local Belgian bands gave him the knowledge to teach others. He knew the works of Wagner and of the Russian National School and brought this late–19th-century sensibility to his own teaching. His gift was one of orchestration and one writer noted ‘Gilson was the first composer of international stature to produce original works for the band that excelled through their mastery of orchestration’ and this skill he taught his students.

Paul Gilson: Poème symphonique en forme d’ouverture (Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force; Matty Cilissen, cond.)

Les Synthétistes wasn’t a style, but, as their name declared, a ‘synthesis of the achievements of contemporary music’, combining old and new techniques. Each composer looked at a different world: Poot, for example, was fascinated by jazz, Debussy’s impressionism, and by Richard Strauss’ humour.

Their commonality was their teacher, Paul Gilson, but their own talents found their own separate paths. Since a unified style wasn’t their goal, they were able to accomplish their larger goal of getting Belgian music into the larger music world. Caught between the two larger countries of The Netherlands and France, Belgium had to fight to make its own name distinctive and Les Synthétistes did their part in the early 19th century.

As the Brussels Seven, they created a new world of wind band music in a country that loved wind band music and it’s only today that we’re starting to rediscover the Seven and their music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I liked the last piece by one of the Seven. 🙂 The audio quality and recording is very good!