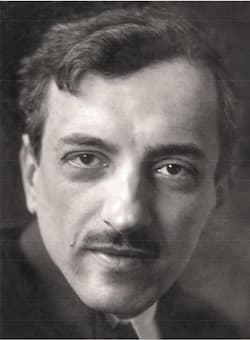

Borys Mykolayovych Lyatoshynsky

Ukrainian composer Borys Mykolayovych Lyatoshynsky (1895-1968) trained with Glière at the Kiev Conservatory and became the most important Ukrainian composer through the mid-20th century. He also taught at the Kiev Conservatory from age 25 through to his death, with occasional stints at the Moscow Conservatory to teach orchestration.

As with many composers writing under Soviet rule, his music was subject to the approval and strictures of the state. Just as Shostakovich and Prokofiev did, he came up against the authorities for his music, with a particular case in his Third Symphony.

Written in 1951, the symphony carried the title of ‘Peace Shall Defeat War,’ and therein lay the problem the authorities had with the work. Lyatoshynsky said the work reflected his creed as an artist: ‘A composer whose voice does not read the heart of the nation has less than no value. I always felt myself to be a national composer in the fullest sense of the word, and I will remain a national composer, proving this not through words but deeds!’

The work was scheduled to have its premiere at the 1951 Congress of the Union of Ukrainian Composers but the performance was cancelled when the work was viewed as ‘anti-Soviet’ and Lyatoshynsky was asked to rewrite the final movement. However, since the score and parts were in the hands of the conductor, Natan Rakhlin, he decided to perform the symphony in open rehearsal. This was 23 October 1951.

It was four years until the rewritten symphony received its premiere in Leningrad on 23 December 1955.

What was the problem with the work? If we think back to the 1950s, it was a time for belligerent posturing on the part of the East and the West. The ‘Cold War’ (1947-1991) was in its early years and declarations of peace were not the mode of the day. A title such as Lyatoshynsky’s would have been an overt declaration at a time when coded whispers were the order of the day.

Borys Lyatoshinsky: Symphony No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 50, “Peace Shall Defeat War” (1951 original version) – I. Andante maestoso (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Kirill Karabits, cond.)

The Soviet censors made Lyatoshynsky go through several rounds of revision. He offered a first revision in 1954 but it took more adjustment before the 1955 premiere could take place.

Borys Lyatoshinsky: Symphony No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 50, “Peace Shall Defeat War” (1951 original version) – II. Andante con moto (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Kirill Karabits, cond.)

The cost to Lyatoshynsky was more than the agony of rewriting what is considered his masterpiece. He was continued to be reviled by the authorities with accusations of ‘formalism, decadence, aggression, sadism and cacophony’ in his music and he didn’t gain his creative freedom again until later in the 1950s.

Borys Lyatoshinsky: Symphony No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 50, “Peace Shall Defeat War” (1951 original version) – III. Allegro feroce (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Kirill Karabits, cond.)

Why did he give in? Other composers, Shostakovich included, just tucked their scores away and waited for a regime change. Lyatoshynsky chose a different path. By rewriting the final to their specifications, the composer ensured that his symphony would be performed. They couldn’t stop performances. The symphony became a favourite and continued to be performed until the early 1990s when the Soviet Union collapsed.

In the 1955 version, the feeling in the final movement is simplified. Tidied. There’s a happy ending.

Borys Lyatoshinsky: Symphony No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 50 – IV. Allegro risoluto (Ukrainian State Symphony Orchestra; Theodore Kuchar, cond.)

However, in the original 1951 version, the surface happiness required of the Soviet authorities is swept away for a more complex sense of resolution.

Borys Lyatoshinsky: Symphony No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 50, “Peace Shall Defeat War” (1951 original version) – IV. Allegro risoluto ma non troppo mosso (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Kirill Karabits, cond.)

The conductor, Kiril Karabits, sees this final movement in its original form as the correct one, because ‘the first three movements do not resolve the tension inherent within them and Lyatoshynsky conceived the structure of the finale as a means to achieve this, conflict giving way to optimism.’

It’s an epic work, with emotions raging from despair to hope and reconciliation. Ukraine suffered doubly in WWII and the post-war era, first from Nazi occupation and then from Soviet suspicion of war-time Nazi collaboration. Lyatoshynsky’s greatest symphony puts all of this in perspective. Peace Shall Defeat War.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter