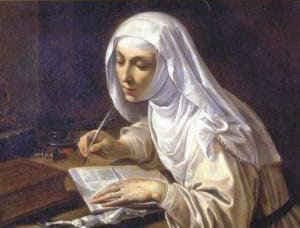

Artemisia Gentileschi: St Cecilia Playing a Lute (ca 1610) (Spada Gallery, Rome), Maddalena Casulana as St. Cecilia

Our history of women composers drops off in between the late 14th century and the mid-16th century. Too much was destroyed across Europe, and too much was lost to be able to construct a rational history.

Fortunately, one of the major developments of the late 15th century was the invention of printing. This means that a unique copy of work could circulate in many copies and along with a work being more widely known, it could have a higher chance of being preserved.

Maddalena Casulana

Maddalena Casulana (c. 1540-c 1590) wrote madrigals and very little about herself. She is thought to have been born near Siena and then probably did her musical training in Florence. She is known for her madrigals and published her first book of madrigals for 4 voices in 1568, the first printed musical work by a woman in western history.

Maddalena Casulana: Vagh’amorosi augelli (Renata Fusco, soprano ; Massimo Lonardi, lute)

Allori: Isabella de’Medici (1558)

(UK: private collection)

Isabella de’Medici

Composers came from all classes, from the nobility, such as Isabella de’Medici (1542-1576) who used her fortune to promote the arts. Maddalena Casulana dedicated more than one piece of music to her, which may imply that Isabella paid for the music as well.

Isabella de’Medici: Lieta vivo et contenta (Lavinia Bertotti, soprano; Maurizio Piantelli, theorbo)

Vittoria/Raphaella Aleotti

Vittoria/Raphaella Aleotti

Vittoria Aleotti and Raphaella Aleotti (c. 1575–ca. 1646) were the same woman. She used the name Vittoria for her secular music, such as her madrigal collection of 1593 and her monastic name, Raphaella, when she published her sacred music. Her father was the architect to the Este court and in his dedication to her madrigal book, wrote that Vittoria/Raphaella and her 4 sisters were educated in music at home before they entered the musical convent of San Vito. Vittoria/Raphaella entered the convent at age 14. She eventually became both the prioress and head of the convent’s musical ensemble.

Raphaella Aleotti: Sacrae cantiones: Diligam te Domine (Cappella Artemisia; Candace Smith, cond.)

Vittoria Alleotti: Ghirlanda de madrigali: Hor che la vaga Aurora (Lavinia Bertotti, soprano; Maurizio Piantelli, theorbo)

Claudia Sessa

Claudia Sessa

Claudia Sessa (ca. 1570–ca 1619) has two songs to her name, both on sacred subjects. Before she was known as a composer, she was a singer, and one of the most famous monastic singers in northern Italy, according to one source. In her setting of a poem by Angelo Grillo, she matches his linguistic cleverness with her own compositional conceits: it is a comparison with the bloody ears of the dying Christ with the vain ornamentation of human ears, and uses surprising cadences and surprise modal shifts to convey the poem’s meaning.

Claudia Sessa: Vattene pur lasciva (Lavinia Bertotti, soprano; Maurizio Piantelli, theorbo)

Again, it is the convents and monasteries that provide the venue for women to be performers and composers. It was also the venue for them to be leaders of musical ensembles. On to the 17th century!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter