The First World War was not merely a global military conflict; it also had far reaching implications for civilian life. It called upon women to become a fundamental part of the war effort, carrying out domestic labor, waged industrial labor, and military nursing and doctoring. It also uprooted millions of European civilians, most of them innocent bystanders.

The First World War was not merely a global military conflict; it also had far reaching implications for civilian life. It called upon women to become a fundamental part of the war effort, carrying out domestic labor, waged industrial labor, and military nursing and doctoring. It also uprooted millions of European civilians, most of them innocent bystanders.

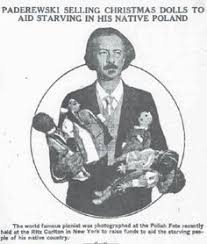

Ignacy Paderewski

While great armies battled against each other across central Europe, Ignacy Paderewski appealed to the world for a dedicated Polish Relief Fund. He wrote, “How can I compose when my Poland is in misery? War is raging over her soil, sweeping away every sign of civilization, destroying dwellings, devastating fields, gardens, and forest, starving and exterminating human beings and animals alike. Only very few could flee to the places which are still holding their own against the aggressors: the great majority, almost eleven millions of helpless women and children, homeless peasants, unemployed workmen, the very essence and strength of a nation, have been driven out into the open. Can one with true patriotism, true love of country, set his mind on something else than the heartrending cries of his people?”

And it was Edward Elgar, too old for active military service, who took up Paderewski’s plea. In 1914, Elgar had written a recitation with orchestra called Carillon for wartime charities in Belgium. He now composed a symphonic prelude titled Polonia, and dedicated it to Paderewski. The work proved immediately popular, and was described as “one of the noblest and most brilliantly beautiful pieces that issued from Elgar’s pen.”

Edward Elgar: Polonia

Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) was called up to serve in the First World War at the age of 42! A rather humorous anecdote reports that an officer demanded to know if “he was this notorious Schoenberg.” Supposedly the composer replied, “Beg to report, sir, yes. Nobody wanted to be, someone had to be, so I let it be me.” Schoenberg was drafted in 1915, and after being trained as a reserve officer, he carried out his military duties as a musician in a military ensemble. The First World War greatly affected all aspects of European society, and that certainly included how composers viewed musical language and their respective approaches to music. In a famous letter to Alma Mahler, Schoenberg severely criticized the bourgeois tendencies of musical reactionaries such as Stravinsky, Ravel and Bizet. Although published as a set, Schoenberg’s Four Orchestral Songs were composed separately. While the first song was finished on 6 October 1913, the final song dates from July of 1916. After finishing this composition—his last works to be written in a free atonal style—Schoenberg issued no new works for the next seven years. He later acknowledged that the “musical emotion, during World War I’s darkest days, is personal, in its feeling of resignation and agitation.” Schoenberg surely has believed that the Rilke poems were addressed directly to him:

I can already sense the storm, and surge like the sea.

And spread myself out and into myself downfall

and hurtle away and am all alone

In the great storm.

Arnold Schoenberg: 4 Orchestral Songs, Op. 22 (Catherine Wyn-Rogers, mezzo-soprano; Philharmonic Orchestra; Robert Craft, cond.)

Gustav Holst

The English composer Gustav Holst (1874-1934) was a highly respected scholar at the Royal College of Music, a professional musician and a teacher. In 1914, and before the beginning of the Great War, Holst had already composed his most famous work, The Planets. Aged 40 when the war broke out, he was past the maximum age limit for volunteers and sported a number of health problems including seriously bad eyesight. The British military rejected him as unfit for service, and Holst resumed his duties as a music educator. Holst felt frustrated that his friends and family were contributing to the war effort, with his close friend Ralph Vaughan Williams serving in France, and his wife enlisted as an ambulance driver. And when his former student George Butterworth perished in the war, Holst was determined to do his bit. He finally got his chance when the YMCA offered Holst a post as Musical Organizer to troops on the Eastern Front waiting for demobilization. First however, he needed to change his name and dropped the “von,” because it looked too Germanic. Eventually he left for Salonica, Greece and taught music and organized concerts for soldiers. On his return, he composed his choral work, Ode to Death, a contemplation on the waste and futility of war, inspired by a Walt Whitman poem. Detailing the futility and terrible waste of life during the First World War, the score bears no dedication. However, his daughter Imogen asserts that at one point it contained the somber dedication “For Cecil Coles, a young composer.” Coles had been killed by a sniper on the Western Front.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gustav Holst: Ode to Death, Op. 38 (London Symphony Chorus; City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)